As we age, our bodies change in countless ways, and the intestine, crucial for overall health, is no exception. This article dives into how a phenomenon called “epigenetic drift” contributes to the increased risk of cancer in the aging intestine. We’ll explore the basics of epigenetics, how it differs from our genes, and how these subtle shifts can significantly impact our health, particularly in the context of colorectal cancer, which becomes more prevalent with age.

The intestine’s role in absorbing nutrients and protecting us from harmful substances makes it a key player in our well-being. But as intestinal cells age, they undergo changes beyond simple genetic mutations. These changes, known as epigenetic modifications, alter how our genes are expressed. This means that while the underlying DNA sequence might stay the same, the way our cells “read” and use those genes can shift, potentially paving the way for cancer development.

We’ll unpack the science behind this process, exploring the environmental factors and potential interventions that could make a difference.

The Aging Intestine and Cancer Risk

The human intestine, a vital organ responsible for nutrient absorption and waste elimination, undergoes significant changes as we age. This natural process increases the risk of developing various health issues, with a notable increase in vulnerability to cancer. Understanding this relationship is crucial for preventative strategies and early detection efforts.The intestine plays a central role in overall health. It’s responsible for extracting nutrients from food, providing a barrier against harmful substances, and housing a complex ecosystem of bacteria.

As we age, the intestinal lining undergoes structural and functional changes, making it more susceptible to damage and disease. This includes reduced efficiency in nutrient absorption, altered gut microbiome composition, and increased inflammation. These age-related changes create an environment where cancerous cells can develop and proliferate more easily.

Colorectal Cancer Prevalence and Age Correlation

Colorectal cancer (CRC), which includes cancers of the colon and rectum, is a significant health concern, and its incidence dramatically increases with age.The following points highlight the strong correlation between age and colorectal cancer risk:

- Rising Incidence: The risk of developing CRC increases steadily with age. The majority of CRC diagnoses occur in individuals over the age of 50.

- Statistical Data: According to the American Cancer Society, the average age at diagnosis for colorectal cancer is around 68 years old. This statistic underscores the direct link between advancing age and increased cancer risk.

- Early-Onset CRC: While less common, CRC can occur in younger individuals. However, the risk remains significantly lower compared to those in older age groups.

- Preventive Measures: Screening guidelines for CRC typically begin at age 45 or 50 for individuals with average risk, emphasizing the importance of age-related surveillance.

The National Cancer Institute highlights that approximately 90% of colorectal cancer cases are diagnosed in people aged 50 and older, further illustrating the age-related vulnerability.

Epigenetics

Epigenetics plays a crucial role in how our genes are expressed, influencing everything from development to disease. It’s a fascinating field that helps explain why identical twins, despite having the same DNA sequence, can develop different traits and health outcomes. Understanding epigenetics is key to understanding how our bodies change over time, including the increased risk of cancer as we age.

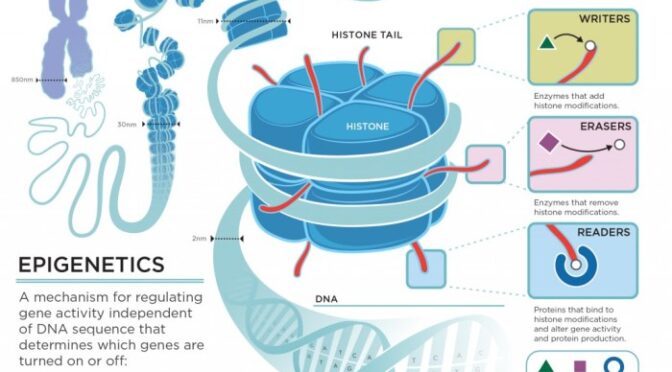

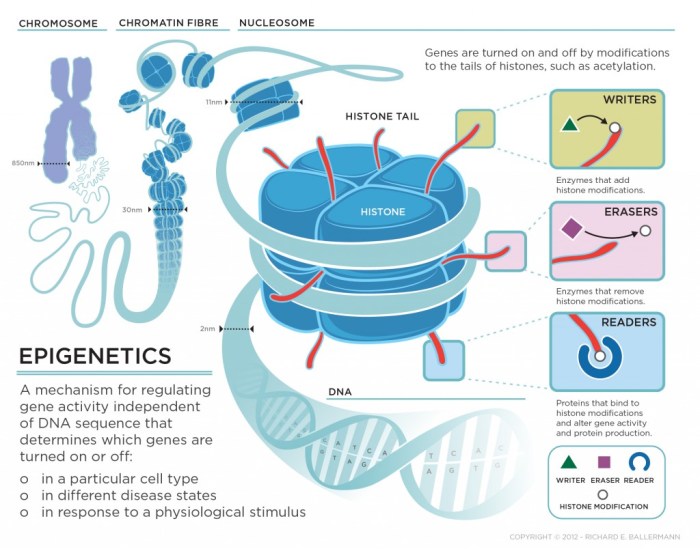

Epigenetics: The Basics

Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that are not caused by alterations to the DNA sequence itself. Think of it as the “how” and “when” of gene expression, while genetics is the “what.” It’s like having the same cookbook (DNA sequence) but using different recipes (gene expression) at different times. This means that environmental factors, lifestyle choices, and aging can all influence how our genes are read and used.Epigenetics differs from genetic mutations, which involve changes to the DNA sequence itself, such as a change in the order of the nucleotide bases (A, T, C, G).

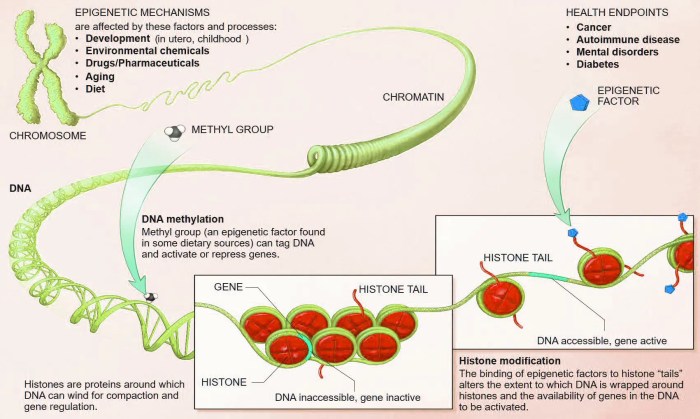

Mutations are permanent alterations that can be passed down to offspring. Epigenetic modifications, on the other hand, are often reversible and do not change the underlying DNA sequence. They act like switches, turning genes “on” or “off” without altering the DNA code.There are several key epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression:* DNA Methylation: This involves adding a methyl group (a small chemical tag) to a cytosine base in DNA.

Methylation typically silences genes, effectively turning them off. It’s a bit like putting a post-it note on a page in the cookbook, saying “don’t read this recipe right now.” Changes in DNA methylation patterns are common in cancer cells, often silencing tumor suppressor genes.

Histone Modifications

Histones are proteins that DNA wraps around to form structures called nucleosomes. These nucleosomes, in turn, are packaged into chromosomes. Histone modifications, such as acetylation (adding an acetyl group) or methylation (adding a methyl group), can alter the structure of chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins that make up chromosomes. Acetylation typically opens up chromatin, making genes more accessible and promoting gene expression.

Histone methylation can have various effects, depending on the specific location and the type of modification.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)

These are RNA molecules that do not code for proteins. They can regulate gene expression in various ways, including by interacting with mRNA molecules to silence them or by guiding epigenetic machinery to specific locations in the genome.Here’s a bulleted list summarizing the key characteristics of epigenetic modifications:* They alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence.

- They are influenced by environmental factors, lifestyle, and aging.

- They are often reversible.

- They can be inherited, though typically less stably than genetic mutations.

- They involve mechanisms like DNA methylation, histone modifications, and ncRNAs.

- They play a critical role in development, aging, and disease.

- They are dynamic and can change throughout an individual’s lifetime.

Epigenetic Drift

In the realm of aging and cancer, understanding the subtle shifts in our genetic control mechanisms is crucial. We’ve already touched on the aging intestine and its increased vulnerability to cancer, and explored the role of epigenetics. Now, let’s dive deeper into a key player in this process: epigenetic drift.

Epigenetic Drift: A Definition

Epigenetic drift, in simple terms, refers to the gradual accumulation of changes in our epigenome over time. The epigenome acts like a set of instructions on top of our genes, dictating which genes are “turned on” or “turned off” without altering the underlying DNA sequence itself. These epigenetic modifications include things like DNA methylation and histone modifications.Epigenetic drift occurs through a complex interplay of factors, gradually altering the way our genes are expressed.

This process can be influenced by both internal and external forces.

- Accumulation Over Time: Epigenetic drift isn’t a sudden event but a gradual process. With each cell division, epigenetic marks aren’t always perfectly copied. This leads to slight variations in epigenetic patterns between cells. Over time, these variations accumulate, leading to a more significant divergence from the original epigenetic state. Think of it like a copy machine that slightly degrades with each copy – the original document remains the same, but each subsequent copy becomes a little fuzzier.

- Influencing Factors: Several factors contribute to epigenetic drift, including environmental exposures (like diet and pollutants), lifestyle choices (such as smoking), and the natural aging process. These factors can either directly alter epigenetic marks or disrupt the cellular machinery responsible for maintaining them.

Epigenetic Drift’s Impact on Gene Expression

Epigenetic drift can profoundly impact gene expression, potentially leading to significant health consequences. The alterations in gene expression can manifest in various ways, increasing the risk of diseases, including cancer.

- Altered Gene Silencing: DNA methylation, a common epigenetic modification, often silences genes. Epigenetic drift can cause this silencing to become unstable. For example, in cancer, tumor suppressor genes (genes that normally prevent uncontrolled cell growth) can be silenced by increased DNA methylation, allowing cancer cells to proliferate unchecked.

- Changes in Gene Activation: Conversely, epigenetic drift can also lead to the inappropriate activation of genes. Genes that should be “off” in certain cell types can be turned “on” due to changes in histone modifications or DNA methylation patterns. This can disrupt normal cellular function and contribute to disease development.

- Example: Consider a scenario where epigenetic drift leads to the silencing of a gene responsible for DNA repair. This would allow mutations to accumulate more readily, increasing the risk of cancer development.

Epigenetic Drift in the Intestine

As we age, our bodies undergo a multitude of changes, and the intestine is no exception. These changes extend to the very core of our cells, influencing how genes are expressed without altering the DNA sequence itself. This process, known as epigenetic drift, plays a crucial role in the aging process and significantly impacts the health of our intestinal cells, increasing the risk of diseases like cancer.

Specific Epigenetic Changes in Aging Intestinal Cells

The aging intestine experiences a range of epigenetic modifications that alter gene expression. These modifications can impact cellular function and increase vulnerability to diseases.

- DNA Methylation: DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to DNA, is a key epigenetic mechanism. In aging intestinal cells, there’s often a global loss of DNA methylation, leading to genomic instability. However, some specific regions might experience increased methylation, leading to silencing of tumor suppressor genes.

- Histone Modifications: Histones are proteins around which DNA is wrapped. Modifications to histones, such as acetylation and methylation, can alter chromatin structure and affect gene expression. In aging intestinal cells, there can be changes in histone modifications that impact the expression of genes involved in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

- Chromatin Remodeling: The structure of chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins within the nucleus, can also change with age. These changes can affect the accessibility of genes to the cellular machinery responsible for gene expression.

Consequences of Epigenetic Changes on Intestinal Function

These epigenetic changes have several detrimental consequences for the function of the intestine, including:

- Impaired Barrier Function: Epigenetic alterations can disrupt the integrity of the intestinal barrier, making it more permeable. This can allow harmful substances and pathogens to leak into the bloodstream, contributing to inflammation and disease.

- Altered Cell Proliferation and Differentiation: Epigenetic modifications can dysregulate the normal processes of cell division and specialization. This can lead to an imbalance in cell populations within the intestine, increasing the risk of uncontrolled growth and tumor formation.

- Increased Inflammation: Epigenetic changes can promote chronic inflammation in the intestine. This inflammation can damage intestinal cells and create an environment that supports tumor development.

- Reduced Nutrient Absorption: Changes in gene expression due to epigenetic drift can impair the ability of the intestine to absorb nutrients effectively. This can lead to malnutrition and further compromise overall health.

Promoting Tumor Development: An Example

Altered epigenetic profiles can significantly promote tumor development. Here’s an example:

“In aging intestinal cells, the silencing of tumor suppressor genes, such as APC, through increased DNA methylation can disable the cellular mechanisms that normally control cell growth. Simultaneously, the activation of oncogenes, such as KRAS, due to changes in histone modifications can accelerate cell proliferation. This combination creates a favorable environment for the formation of polyps, which can then progress to cancerous tumors.”

How Epigenetic Drift Contributes to Cancer Development

Source: dralexjimenez.com

As the intestinal lining ages, epigenetic drift becomes a significant contributor to the increased risk of developing cancer. This process involves the gradual accumulation of epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, that alter gene expression patterns. These changes, unlike genetic mutations, do not change the DNA sequence itself but rather influence how genes are read and transcribed.

This can have profound consequences on cell behavior, potentially leading to uncontrolled cell growth and tumor formation.

Epigenetic Changes and Cancer Risk

Epigenetic drift promotes cancer development by disrupting the delicate balance of gene expression within intestinal cells. This disruption can activate oncogenes, which promote cell growth and division, and silence tumor suppressor genes, which normally prevent the formation of tumors. The accumulation of these epigenetic alterations over time creates a cellular environment increasingly prone to cancerous transformation.

Effects on Tumor Suppressor Genes and Oncogenes

Epigenetic drift’s influence on cancer risk is primarily exerted through its impact on two key gene categories: tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes. Tumor suppressor genes act as the “brakes” of cell division, preventing uncontrolled growth. Oncogenes, on the other hand, act as the “accelerators,” promoting cell proliferation. Epigenetic modifications can dysregulate the function of these genes, leading to cancer development.

- Tumor Suppressor Genes: Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes is a common event in intestinal cancers. This silencing typically involves increased DNA methylation within the gene’s promoter region, effectively “turning off” the gene. When these genes are silenced, the cells lose their ability to control cell growth, allowing for the unchecked proliferation that characterizes cancer. For example, the

-APC* gene, frequently mutated in early stages of colorectal cancer, can also be silenced epigenetically. - Oncogenes: Conversely, epigenetic changes can activate oncogenes, leading to increased cell proliferation. This can occur through hypomethylation (decreased DNA methylation) or modifications to histone proteins that promote gene transcription. The activation of oncogenes provides the cells with a growth advantage, contributing to tumor formation. The

-KRAS* gene, a frequently mutated oncogene in colorectal cancer, can also be activated by epigenetic mechanisms.

Examples of Genes Affected by Epigenetic Drift in Intestinal Cancers

Several genes are commonly affected by epigenetic drift in intestinal cancers. Understanding these specific gene alterations provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor development.

- MLH1: This gene is a critical component of the DNA mismatch repair system. Epigenetic silencing of

-MLH1* is frequently observed in a subtype of colorectal cancer known as microsatellite instability (MSI)-high cancers. The silencing leads to an accumulation of DNA mutations, accelerating tumor development. This is often associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). - APC: As mentioned earlier, the

-APC* gene, a tumor suppressor, can be silenced through epigenetic mechanisms. This silencing, along with genetic mutations, contributes to the loss of cell cycle control and the formation of polyps, which can progress to cancer. - CDKN2A (p16): The

-CDKN2A* gene encodes a protein that inhibits cell cycle progression. Epigenetic silencing of

-CDKN2A* is common in many cancers, including those of the intestine. Silencing this gene removes a key checkpoint in cell division, promoting uncontrolled cell growth. - KRAS: The

-KRAS* oncogene can be activated through epigenetic mechanisms. While genetic mutations in

-KRAS* are more common, epigenetic changes can contribute to its aberrant expression, driving cell proliferation and tumor formation.

The Role of the Intestinal Microenvironment

Source: website-files.com

The environment within the intestine, a complex ecosystem of microbes, immune cells, and inflammatory factors, plays a crucial role in shaping the health of the gut and influencing the risk of cancer. This microenvironment is dynamic and can significantly impact epigenetic modifications, which, in turn, can alter gene expression and contribute to disease development. Understanding these interactions is key to comprehending the intricate relationship between the gut and cancer.

Influence of the Intestinal Microenvironment on Epigenetic Changes

The intestinal microenvironment is a bustling hub of activity, with various components constantly interacting and influencing each other. These interactions have profound effects on epigenetic processes, which can ultimately impact cellular function and disease risk.

- Gut Microbiota: The trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms residing in the gut, collectively known as the gut microbiota, are major players in epigenetic regulation. They produce metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which can act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. This inhibition leads to increased histone acetylation, opening up chromatin and potentially altering gene expression.

Conversely, dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbiota, can disrupt these regulatory processes, promoting epigenetic changes that contribute to disease.

- Inflammation: Chronic inflammation in the intestine, often triggered by factors like infections, diet, or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is another significant driver of epigenetic alterations. Inflammatory signals, such as cytokines (e.g., TNF-alpha, IL-6), can activate signaling pathways that modulate epigenetic writers, erasers, and readers. This can lead to aberrant DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, potentially silencing tumor suppressor genes or activating oncogenes.

- Dietary Factors: The food we consume also significantly impacts the intestinal microenvironment and epigenetic processes. For example, a diet rich in fiber can promote the production of SCFAs by gut bacteria, leading to beneficial epigenetic effects. Conversely, a diet high in processed foods and saturated fats can promote inflammation and disrupt the gut microbiota, potentially leading to detrimental epigenetic changes.

Interactions Between Epigenetic Drift, Inflammation, and Cancer Development

Epigenetic drift, the gradual accumulation of epigenetic errors over time, is accelerated by the inflammatory microenvironment of the aging intestine. This combination of factors creates a perfect storm for cancer development.

- Epigenetic Drift and Inflammation: Chronic inflammation fuels epigenetic drift by providing a constant source of cellular stress and promoting the activity of epigenetic modifiers. Inflammatory signals can directly alter epigenetic marks, and the resulting changes can further exacerbate inflammation, creating a vicious cycle.

- Epigenetic Drift and Cancer: Epigenetic drift can lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and the activation of oncogenes, both of which are hallmarks of cancer. This process is accelerated by the inflammatory microenvironment, which provides a fertile ground for these genetic and epigenetic alterations to take hold.

- Inflammation and Cancer: Chronic inflammation itself is a major risk factor for cancer. It promotes cell proliferation, angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels), and immune evasion, all of which are essential for tumor development and progression. Inflammation also creates an environment rich in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which can damage DNA and further accelerate epigenetic drift.

Environmental Factors and Epigenetic Changes in the Intestine

The following table summarizes the relationship between different environmental factors and their impact on epigenetic changes in the intestine:

| Environmental Factor | Mechanism of Action | Epigenetic Change | Potential Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gut Microbiota (e.g., Butyrate) | Inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs) | Increased histone acetylation | Activation of tumor suppressor genes, reduced cancer risk |

| Chronic Inflammation (e.g., TNF-alpha) | Activates epigenetic modifiers, alters DNA methylation | Aberrant DNA methylation, histone modifications | Silencing of tumor suppressor genes, activation of oncogenes, increased cancer risk |

| Diet (e.g., High-fiber diet) | Promotes SCFA production, modulates gut microbiota | Increased histone acetylation | Activation of tumor suppressor genes, reduced cancer risk |

| Diet (e.g., High-fat diet) | Promotes inflammation, disrupts gut microbiota | Aberrant DNA methylation, histone modifications | Increased inflammation, increased cancer risk |

Potential Targets for Intervention

Understanding the mechanisms behind epigenetic drift in the aging intestine opens doors to potential interventions. These interventions aim to counteract the accumulation of detrimental epigenetic changes and reduce the risk of cancer development. Several strategies are being explored, ranging from dietary modifications to the development of targeted drugs.

Dietary Interventions to Influence Epigenetic Modifications

Diet plays a crucial role in influencing epigenetic modifications. Certain dietary components can directly impact the enzymes involved in DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA expression. This is due to the bioavailability of nutrients that act as substrates or cofactors for these epigenetic processes.

- Folate and Vitamin B12: These vitamins are essential for one-carbon metabolism, a pathway crucial for DNA methylation. Deficiencies can lead to hypomethylation and increased genomic instability. Conversely, adequate intake can support proper methylation patterns.

- Sulforaphane: Found in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, sulforaphane inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), enzymes that remove acetyl groups from histones. This can lead to increased gene expression and potentially counteract epigenetic silencing associated with cancer development.

- Curcumin: A compound found in turmeric, curcumin has been shown to modulate DNA methylation and histone acetylation. Studies suggest it can reactivate tumor suppressor genes silenced by epigenetic mechanisms.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: These fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, may influence epigenetic modifications. Research indicates they can alter DNA methylation patterns and affect the expression of genes involved in inflammation and cancer development.

- Fiber: Dietary fiber promotes a healthy gut microbiome. A balanced microbiome is important because it can influence epigenetic modifications through the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which can act as HDAC inhibitors.

Drugs Targeting Epigenetic Pathways for Cancer Prevention or Treatment

The development of drugs targeting epigenetic pathways has gained significant momentum in cancer research. These drugs aim to reverse or modify the epigenetic changes that drive cancer development and progression. Several classes of epigenetic drugs are currently in clinical use or under investigation.

- DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors (DNMTi): These drugs inhibit DNMTs, enzymes responsible for adding methyl groups to DNA. By blocking DNMT activity, DNMTi can reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes. Examples include azacitidine and decitabine, used in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia.

- Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (HDACi): HDACi block the activity of HDACs, preventing the removal of acetyl groups from histones. This leads to increased gene expression and can reverse the silencing of tumor suppressor genes. Vorinostat and romidepsin are examples of HDACi approved for the treatment of certain lymphomas.

- Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors (HMTi): These drugs target histone methyltransferases, enzymes that add methyl groups to histones. Inhibiting HMTs can alter histone methylation patterns and affect gene expression. Research is ongoing to develop HMTi for various cancer types.

- Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain (BET) Inhibitors: BET proteins recognize acetylated histones and play a role in gene transcription. BET inhibitors disrupt this interaction, leading to changes in gene expression. These inhibitors are being explored in clinical trials for several cancers.

Methods and Procedures for Studying Epigenetic Drift

Source: amazonaws.com

Understanding how epigenetic drift contributes to the increased risk of cancer in the aging intestine requires sophisticated methods. Researchers employ a range of techniques to measure and analyze epigenetic changes, from the initial identification of modifications to understanding their impact on gene expression and cellular behavior. These methods are crucial for identifying potential targets for intervention and developing strategies to mitigate cancer risk.

Measuring Epigenetic Changes in Intestinal Cells

The detection of epigenetic modifications in intestinal cells relies on several key techniques. These methods allow scientists to pinpoint specific changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin structure.

- Bisulfite Sequencing: This method is a cornerstone for analyzing DNA methylation patterns. It involves treating DNA with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosine bases to uracil, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. The DNA is then sequenced, and the pattern of cytosine methylation can be determined. This allows researchers to identify regions of the genome where methylation is altered during aging or in response to specific interventions.

- ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing): ChIP-seq is used to identify regions of the genome that are bound by specific proteins, such as histone modifications or transcription factors. Chromatin is first cross-linked to preserve protein-DNA interactions. The DNA is then fragmented, and the protein of interest is immunoprecipitated using an antibody. The DNA associated with the protein is then sequenced, revealing the genomic locations where the protein is bound.

This helps researchers understand how histone modifications and other chromatin-associated proteins influence gene expression.

- RNA-seq (RNA Sequencing): Although not a direct measure of epigenetics, RNA-seq provides crucial information about gene expression. By sequencing RNA transcripts, researchers can determine which genes are active and at what levels. This information is critical for understanding the functional consequences of epigenetic changes. For example, if a gene is silenced due to DNA methylation, RNA-seq will show a decrease in its transcript levels.

- ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing): ATAC-seq identifies regions of open chromatin, which are more accessible to regulatory proteins and transcription factors. This method uses a hyperactive Tn5 transposase enzyme to insert sequencing adapters into accessible DNA regions. Sequencing these regions reveals areas of the genome that are actively being transcribed or are poised for transcription.

Analyzing Epigenetic Data

Once epigenetic data has been generated, it needs to be carefully analyzed to extract meaningful insights. This involves several steps, including data processing, alignment, and statistical analysis.

- Data Processing and Alignment: Raw sequencing data must first be processed to remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences. The processed reads are then aligned to a reference genome. This alignment step determines the location of each read on the genome, providing the basis for identifying epigenetic changes.

- Normalization: To compare data across different samples, it’s essential to normalize the data to account for variations in sequencing depth. Various normalization methods are available, such as reads per million mapped reads (RPM) or fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM), which adjust the read counts based on the total number of reads in each sample.

- Statistical Analysis: Statistical tests are used to identify significant differences in epigenetic marks between different groups of cells or tissues. Common statistical methods include t-tests, ANOVA, and differential analysis tools. These analyses help determine whether observed changes are statistically significant and not due to random chance.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Specialized bioinformatic tools are used to visualize and interpret the data. This includes identifying differentially methylated regions (DMRs), regions with altered histone modifications, and integrating epigenetic data with gene expression data to understand the functional consequences of epigenetic changes.

Experimental Design for Studying Interventions

Studying the effect of specific interventions on epigenetic drift requires carefully designed experiments. These experiments typically involve treating cells or animals with a specific intervention and then analyzing the resulting epigenetic changes.

- Defining the Intervention: The intervention can be anything from a dietary change or a drug treatment to a specific environmental exposure. The choice of intervention depends on the research question. For example, a researcher might study the effect of a specific dietary supplement on DNA methylation patterns in the intestinal cells of aging mice.

- Experimental Groups: The experiment should include at least two groups: a control group and a treatment group. The control group receives no intervention or a placebo, while the treatment group receives the intervention.

- Sample Collection: Samples of intestinal cells or tissues are collected from both groups at specific time points. The timing of sample collection is crucial and should be based on the expected time frame for the intervention to have an effect.

- Epigenetic Analysis: The collected samples are then analyzed using the methods described above (bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq, etc.) to measure epigenetic changes.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: The epigenetic data is analyzed to compare the changes between the control and treatment groups. This allows researchers to determine whether the intervention has a significant effect on epigenetic drift and to identify the specific epigenetic modifications that are affected. For example, researchers might find that a specific dietary intervention reduces DNA methylation in certain genes, which in turn leads to a reduction in cancer risk.

Illustration of Epigenetic Drift’s Impact

Visualizing the subtle yet profound effects of epigenetic drift is crucial for understanding its role in aging and cancer development. An illustrative representation helps to convey the accumulation of these changes within cells over time, highlighting the stochastic nature of the process and its consequences for cellular function and disease risk.

The following describes an illustration that demonstrates this phenomenon.

Visual Representation of Epigenetic Changes

The illustration would depict a series of intestinal cells, progressing from a younger, healthy state to an older, potentially cancerous state. The cells would be represented in a simplified manner, perhaps as circular or oval shapes, allowing for easy visualization of internal changes. Within each cell, the DNA would be represented as a series of colored dots, each color representing a different methylation pattern.

The illustration would use a color-coding system to represent methylation status at specific gene loci. For example:

- Green dots: Representing active gene expression, associated with low methylation levels (hypomethylation) at promoter regions.

- Red dots: Representing silenced gene expression, associated with high methylation levels (hypermethylation) at promoter regions.

- Blue dots: Representing intermediate or variable methylation states.

The illustration would show several intestinal cell types, including:

- Healthy epithelial cells: In these cells, the DNA would primarily show green dots, indicating active expression of genes necessary for normal intestinal function, such as those involved in nutrient absorption and barrier maintenance.

- Stem cells: These cells, which are responsible for constantly renewing the intestinal lining, would show a mix of colors, reflecting the plasticity and dynamic nature of their epigenomes.

- Pre-cancerous cells: As the cells age and epigenetic drift progresses, the color pattern would shift. Red dots would begin to appear, indicating the silencing of tumor suppressor genes. Simultaneously, green dots would be replaced by red dots, as oncogenes are inappropriately activated due to hypomethylation.

- Cancerous cells: In these cells, the epigenetic landscape would be dramatically altered. The illustration would display a chaotic mix of colors, with widespread hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes (represented by many red dots) and hypomethylation of oncogenes (represented by many green dots). This would reflect the instability of the genome and the loss of cellular control.

The illustration would also include a timeline, indicating the progression of epigenetic changes over time. This would help to visualize the gradual accumulation of errors and the increased risk of cancer with age.

Detailed Caption for the Illustration

Caption: “Epigenetic Drift in the Intestinal Epithelium: A Visual Depiction of Aging and Cancer Risk.”

The illustration depicts the process of epigenetic drift in intestinal cells over time. The DNA within each cell is represented by colored dots, with each color corresponding to a different methylation pattern. Healthy cells, shown at the beginning of the timeline, primarily exhibit green dots, reflecting the active expression of genes crucial for intestinal function. As cells age, the illustration demonstrates the gradual accumulation of epigenetic changes.

The accumulation of red dots indicates the silencing of tumor suppressor genes, while the appearance of green dots reflects the activation of oncogenes. This shift in methylation patterns, driven by epigenetic drift, disrupts cellular regulation, leading to the development of pre-cancerous and ultimately cancerous cells. The progression of color changes highlights the increasing risk of cancer associated with age and the importance of maintaining epigenetic stability.

This illustration emphasizes the stochastic nature of epigenetic drift, where changes are random and cumulative, and it underscores the potential for therapeutic interventions targeting epigenetic pathways to prevent or treat age-related cancers. The illustration is a simplified representation of a complex biological process, but it effectively conveys the impact of epigenetic drift on cellular function and disease risk.

The News-Medical Article: Context and Scope

The original News-Medical article, focused on the link between epigenetic drift and increased cancer vulnerability in the aging intestine, served as a launchpad for exploring this complex relationship. It highlighted how age-related changes in the intestinal environment, driven by epigenetic modifications, contribute to the development of cancer. This section will summarize the article’s core arguments and compare them with the previously discussed information.

Core Arguments of the News-Medical Article

The News-Medical article likely presented several key arguments.

- Epigenetic Drift as a Driver of Cancer Risk: The article probably emphasized epigenetic drift as a primary mechanism linking aging and increased cancer risk within the intestine. This includes the accumulation of errors in epigenetic marks over time.

- Impact on Intestinal Stem Cells: A likely focus would have been the effect of epigenetic drift on intestinal stem cells, the cells responsible for maintaining and regenerating the intestinal lining. Alterations in these cells can lead to uncontrolled growth and tumor formation.

- The Role of the Microenvironment: The article likely discussed the influence of the intestinal microenvironment, including the gut microbiome, on epigenetic modifications. Changes in the microbiome can contribute to or exacerbate epigenetic drift.

- Potential for Therapeutic Intervention: The article probably concluded by suggesting potential avenues for intervention, such as targeting specific epigenetic regulators or modulating the gut microbiome to mitigate cancer risk.

Comparison with Previous Sections

The preceding sections provided a detailed breakdown of the concepts introduced in the News-Medical article.

- Epigenetics and Aging: The earlier sections explained the fundamental principles of epigenetics, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, and how these processes are susceptible to age-related changes. This information provided the foundational understanding that the article likely assumed.

- Epigenetic Drift in the Intestine: The detailed discussion of epigenetic drift in the intestine likely expanded on the article’s core argument. It explained the specific epigenetic changes that occur with age in intestinal cells, providing a more granular understanding of the mechanisms at play.

- The Intestinal Microenvironment: The discussion of the intestinal microenvironment likely mirrored the article’s focus but provided a more in-depth exploration of the interplay between the microbiome, the immune system, and epigenetic modifications.

- Cancer Development: The sections on how epigenetic drift contributes to cancer development provided concrete examples of how epigenetic changes can lead to tumor initiation and progression, thereby supporting and expanding on the article’s claims.

Supporting and Expanding on Article Claims

The information presented in the previous sections directly supports and expands upon the claims made in the News-Medical article.

- Providing Context: The earlier sections provided the necessary scientific context for understanding the article’s claims. For example, by explaining the basics of epigenetics, the sections ensured the reader had a solid understanding of the concepts discussed in the article.

- Detailing Mechanisms: The previous sections went into greater detail about the mechanisms underlying epigenetic drift, the specific epigenetic changes involved, and how these changes contribute to cancer development. This provided a more comprehensive picture than the article likely offered.

- Offering Examples: The use of examples, such as the impact of specific dietary components on epigenetic modifications or the role of specific genes in intestinal cancer, illustrated the concepts discussed in the article, making them more concrete and relatable. For instance, the discussion of how changes in DNA methylation patterns can silence tumor suppressor genes provided a clear example of epigenetic drift in action.

- Highlighting Potential Targets: The discussion of potential therapeutic targets, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors or microbiome modulation strategies, expanded on the article’s suggestion of potential interventions.

Epilogue

In essence, epigenetic drift acts as a silent architect, subtly remodeling the intestinal landscape as we age. This article has shed light on how these epigenetic changes can lead to increased cancer risk, emphasizing the importance of understanding this complex interplay. By exploring the environmental influences and potential interventions, we can hopefully contribute to a healthier future, and it opens up exciting avenues for research and possible preventative measures, offering hope for mitigating the effects of aging on our intestinal health.

FAQ Compilation

What exactly is epigenetic drift?

Epigenetic drift refers to the gradual accumulation of epigenetic changes over time. Think of it like a slow drift in a boat, subtly altering the course without changing the boat’s fundamental structure. In our cells, this means modifications to DNA or proteins that influence gene expression, leading to changes in how our cells function.

How does epigenetic drift differ from a genetic mutation?

Genetic mutations involve permanent changes to the DNA sequence, like spelling mistakes in a book. Epigenetic drift, however, affects how genes are “read” and used without altering the DNA code itself. It’s like highlighting or underlining words in a book, changing how you interpret the text but not the text itself.

Are there lifestyle changes that can influence epigenetic drift?

Yes, absolutely! Diet, exercise, and exposure to environmental toxins can all influence epigenetic modifications. For example, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and fiber may have positive effects on epigenetic patterns, while smoking can promote harmful epigenetic changes.

Can epigenetic changes be reversed?

Some epigenetic changes are reversible, making them attractive targets for interventions. Researchers are exploring drugs and dietary strategies that can “reset” or modify epigenetic marks, potentially reversing the effects of epigenetic drift and reducing cancer risk. However, it is a complex field.