Rewriting history is a complex phenomenon, a deliberate reshaping of the past that affects how we understand the present. It’s a practice as old as recorded history itself, evolving with societies and driven by a variety of motivations. This exploration will delve into the core elements of rewriting history, examining its various forms and the intentions behind it.

We’ll unpack the methods employed, from subtle omissions to outright fabrication, and analyze the impact of technology on the spread of revised narratives. From political machinations to cultural biases, we will investigate the driving forces behind these historical manipulations, providing real-world examples to illustrate the complexities of this practice. Furthermore, this exploration includes case studies and the effects and countermeasure that will make it more comprehensive.

Defining “Rewriting History”

Source: inkforall.com

Rewriting history involves deliberately altering or manipulating the historical record. This process aims to reshape our understanding of the past, often to serve a particular agenda or ideology. It can manifest in various forms, ranging from subtle omissions to outright fabrication, and can have significant consequences for how societies perceive themselves and the world.

Core Elements of Rewriting History

The core elements of rewriting history center on the intentional distortion of past events. This distortion is achieved through selective presentation, suppression, or invention of historical facts. The goal is always to create a narrative that aligns with a specific viewpoint or serves a particular purpose. It fundamentally involves changing the accepted version of events, often by emphasizing certain aspects while downplaying or eliminating others.

Forms of Rewriting History

Rewriting history takes on several forms, each with its own characteristics and impacts. These methods are not mutually exclusive and can often be used in combination.

- Omission: This involves leaving out key events, individuals, or perspectives from the historical narrative. By selectively omitting information, a particular interpretation of the past can be promoted. For example, a textbook might fail to mention the contributions of a minority group to a significant historical event, thereby minimizing their role and influence.

- Exaggeration: Exaggeration involves amplifying certain aspects of events or the actions of individuals to create a desired impression. This can involve inflating numbers, emphasizing heroic deeds, or demonizing opponents. Propaganda often utilizes exaggeration to sway public opinion. An example is exaggerating the success of a military campaign or inflating the economic growth figures.

- Revisionism: Revisionism entails reinterpreting historical events or figures in light of new evidence or ideological perspectives. While legitimate historical revisionism, based on new discoveries, is a natural part of historical scholarship, manipulative revisionism often distorts facts to fit a pre-determined agenda. This could involve reinterpreting the causes of a war or the motivations of a historical figure to cast them in a more favorable light.

- Fabrication: This involves the outright creation of false historical information, including documents, events, or claims. Fabrication is a blatant form of rewriting history and is often used to promote propaganda or justify political actions. The forging of documents to incriminate an opponent is a prime example.

- Misrepresentation: Misrepresenting historical events involves presenting them in a misleading way, often by taking them out of context or distorting their meaning. This can involve using biased language, cherry-picking evidence, or creating false associations. For instance, using a single quote from a historical figure to portray them as supporting a position they never held.

Intentions Behind Rewriting History

The intentions behind rewriting history are varied, but they generally serve to achieve specific goals. These intentions often relate to political power, social control, or the promotion of particular ideologies.

- Political Legitimacy: Rewriting history can be used to legitimize a government or political regime. By creating a narrative that supports the current power structure, leaders can strengthen their position and maintain control. This is often achieved by portraying the past in a way that validates the current policies or actions.

- Nationalism and Identity: History is frequently rewritten to foster a sense of national identity and unity. By emphasizing shared experiences, heroic figures, and a glorious past, a nation can be built and maintained. This often involves selectively highlighting positive aspects of the past while downplaying negative ones.

- Ideological Promotion: Rewriting history can be used to promote a particular ideology or set of beliefs. This can involve emphasizing events or figures that support the ideology while suppressing those that contradict it. For example, a communist regime might rewrite history to highlight the achievements of the working class while downplaying the suffering under their rule.

- Social Control: By controlling the narrative of the past, those in power can control the present and the future. This can be achieved by shaping public opinion, suppressing dissent, and discouraging critical thinking. A government that controls the historical narrative can influence how people perceive their place in society and their relationship to the state.

- Economic Gain: History can be rewritten for economic purposes. This could involve promoting a particular version of the past to encourage tourism, justify economic policies, or protect a country’s reputation. For instance, a country might emphasize its historical role in trade to attract foreign investment.

Methods of Historical Revision

Historical revision, the act of reinterpreting past events, is a complex process with various methods employed to alter the understanding of history. These methods, often intertwined, can range from subtle shifts in emphasis to outright fabrication, all with the goal of shaping the narrative to serve a specific agenda. Understanding these techniques is crucial to critically evaluate historical information and discern the underlying motivations behind historical accounts.

Propaganda and Censorship

Propaganda and censorship are powerful tools used to rewrite history by controlling the flow of information. Propaganda aims to influence public opinion by selectively presenting information, often with a bias or outright falsehoods, to promote a particular viewpoint. Censorship, on the other hand, actively suppresses information deemed undesirable, preventing alternative perspectives from reaching the public.

“History is written by the victors,”

a phrase often attributed to Winston Churchill, highlights the impact of propaganda and censorship. The victors of conflicts often control the narrative, shaping the historical record to portray themselves favorably while demonizing their opponents. This can involve exaggerating achievements, downplaying failures, and omitting inconvenient truths. Censorship complements propaganda by removing dissenting voices and alternative interpretations, ensuring the dominant narrative remains unchallenged.

Both methods work together to create a controlled environment where the official version of history prevails.

Manipulation of Sources

The manipulation of historical sources is another common method used in historical revision. This can take many forms, from selectively quoting sources to outright forging documents. The goal is to present a skewed picture of the past by altering or misrepresenting the available evidence.This manipulation can involve:

- Selective Quotation: Presenting only parts of a source that support a particular argument while omitting contradictory information.

- Misinterpretation: Misunderstanding or deliberately misrepresenting the meaning of a source to fit a desired narrative.

- Fabrication: Creating entirely new sources, such as documents or artifacts, to support a false claim.

- Destruction: Destroying or concealing sources that contradict the desired narrative.

These tactics undermine the reliability of historical accounts and make it difficult to reconstruct an accurate picture of the past. By controlling the evidence, those seeking to revise history can shape the narrative to their liking, regardless of the truth.

Examples of Historical Events Subject to Revision

The following table provides examples of historical events that have been subject to revision, demonstrating the various methods employed.

| Original Event | Revised Narrative | Group/Entity Responsible | Methods Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945) | Justification for the bombings, emphasizing the saving of American lives and the ending of the war. | The United States Government | Propaganda, Selective Emphasis on Japanese Atrocities, Censorship of opposing viewpoints. |

| The Holocaust (1941-1945) | Denial or minimization of the Holocaust, claiming it was exaggerated or fabricated. | Neo-Nazis, Holocaust Deniers | Fabrication of “evidence,” selective use of historical sources, censorship of opposing views. |

| The Russian Revolution (1917) | Soviet versions: Glorification of the revolution and its leaders; revisionist versions: Emphasis on the negative consequences and repression. | Soviet Government (historical accounts), Various modern historians | Propaganda, Censorship, Manipulation of Sources, Selective Interpretation of Events. |

| The American Civil War (1861-1865) | “Lost Cause” narrative: Romanticized view of the Confederacy, downplaying slavery as the primary cause of the war. | Confederate veterans’ organizations, White supremacist groups | Propaganda, Selective Interpretation of Events, Manipulation of Sources. |

Impact of Technological Advancements

Technological advancements have significantly impacted the ease and spread of historical revision. The rise of social media and digital archives has created both opportunities and challenges for historical accuracy.The impact of technological advancements include:

- Social Media: Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube allow for the rapid dissemination of information, including revised historical narratives, often without proper fact-checking. This can lead to the spread of misinformation and the formation of echo chambers where biased viewpoints are reinforced.

- Digital Archives: The digitization of historical documents and archives makes primary sources more accessible to a wider audience. However, it also makes it easier to manipulate these sources, such as by altering digital images or creating fake documents.

- Online Forums and Blogs: Online platforms facilitate discussions about history, but they also provide spaces for the proliferation of revisionist narratives and conspiracy theories. The lack of editorial oversight on many of these platforms allows for the unchecked spread of false information.

- AI and Deepfakes: The development of artificial intelligence has enabled the creation of sophisticated “deepfakes”

-manipulated videos and audio recordings that can be used to spread false information and revise historical events. This technology poses a significant threat to historical accuracy. For example, a deepfake video could be created to falsely portray a historical figure making a controversial statement.

Motivations Behind Historical Revision

Historical revisionism isn’t a neutral exercise; it’s often driven by powerful forces seeking to shape how we understand the past. These motivations can be broadly categorized into political, economic, and cultural/ideological drivers, each playing a significant role in influencing the narratives that dominate public consciousness. Understanding these motivations is crucial to critically evaluating historical accounts.

Political Motivations

Governments frequently employ historical revisionism to consolidate power, legitimize their actions, and control public opinion. This often involves rewriting historical events to portray the current regime in a favorable light, demonize opponents, or foster a sense of national unity.

- Legitimizing Authority: Authoritarian regimes commonly rewrite history to portray themselves as the natural or inevitable rulers. This can involve downplaying past atrocities, exaggerating achievements, or fabricating a continuous lineage of power.

For example, North Korea’s official history heavily glorifies the Kim dynasty, portraying them as heroic leaders who liberated the country and brought prosperity. This narrative serves to legitimize their rule and suppress dissent.

- Promoting Nationalism: Historical revisionism is often used to create a shared national identity and foster patriotism. This might involve emphasizing glorious past events, downplaying negative aspects of a nation’s history, and creating common enemies.

The Turkish government’s interpretation of the Armenian Genocide is a clear example. While acknowledging the deaths of Armenians during World War I, the official narrative often denies the intent to exterminate, downplays the scale of the atrocities, and frames the events within the context of war and unrest. This serves to promote a sense of national unity and deflect criticism.

- Demonizing Opponents: Governments frequently revise history to discredit political opponents, both domestic and foreign. This can involve portraying them as traitors, incompetent leaders, or agents of external forces.

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in historical revisionism to portray each other as the primary aggressor and threat to world peace. This involved selectively highlighting events, manipulating facts, and spreading propaganda to undermine the other side’s legitimacy.

- Justifying Current Policies: Historical narratives are often manipulated to justify current political decisions. This might involve drawing parallels between past events and present circumstances to create a sense of urgency or inevitability.

The use of the “Munich analogy” in the lead-up to the Iraq War, where Saddam Hussein was compared to Adolf Hitler, is a prominent example. This historical comparison was used to justify military intervention, despite significant differences between the two situations.

Economic Interests

Economic interests significantly influence historical narratives, as certain industries and groups benefit from specific interpretations of the past. This can involve promoting narratives that support free markets, downplaying the negative consequences of industrialization, or glorifying figures who advanced particular economic interests.

- Promoting Free Market Ideology: Historical revisionism often serves to promote free-market capitalism by downplaying the negative effects of unregulated markets, such as worker exploitation and environmental degradation. This can involve glorifying industrialists and entrepreneurs, and portraying government regulation as an impediment to progress.

The portrayal of figures like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller in American history often emphasizes their philanthropic contributions and entrepreneurial spirit, while downplaying the harsh working conditions and monopolistic practices that characterized their businesses. This narrative serves to legitimize free-market capitalism.

- Protecting Corporate Interests: Industries frequently engage in historical revisionism to protect their interests, such as denying the harmful effects of their products or downplaying their role in environmental damage.

The tobacco industry’s long-term denial of the link between smoking and cancer is a well-documented example. The industry used historical revisionism to create doubt and confusion about the scientific evidence, thereby delaying regulation and protecting its profits.

- Shaping Labor History: Economic interests often shape the narrative of labor history. This might involve downplaying the struggles of workers, demonizing labor unions, or glorifying business owners.

The portrayal of labor unions in some historical accounts often focuses on their negative impacts, such as strikes and disruptions, while downplaying their role in improving working conditions and securing workers’ rights.

Cultural and Ideological Biases

Cultural and ideological biases deeply influence how history is written and interpreted. These biases can arise from various sources, including religious beliefs, ethnic identity, gender, and social class.

- Religious Bias: Religious beliefs can significantly shape historical narratives, leading to the promotion of specific religious figures or the demonization of opposing faiths.

Historical accounts of the Crusades, for example, often reflect a Christian perspective, portraying the crusaders as heroes and downplaying the suffering inflicted on Muslims and Jews. Conversely, some Muslim accounts might portray the Crusades differently, emphasizing the violence and brutality of the Christian armies.

- Ethnic and Racial Bias: Historical narratives are often shaped by ethnic and racial biases, leading to the marginalization or misrepresentation of certain groups.

The history of colonialism is often written from the perspective of the colonizers, downplaying the suffering and exploitation of colonized peoples. This can involve glorifying colonial achievements, ignoring the negative consequences of colonialism, and portraying indigenous populations as inferior.

- Gender Bias: Traditional historical accounts often focus on the achievements of men, while neglecting the contributions of women.

The history of science, for example, often highlights the contributions of male scientists while downplaying the role of women scientists. This can lead to a distorted understanding of the past.

- Ideological Bias: Political ideologies, such as conservatism, liberalism, and socialism, can shape historical interpretations. This can involve emphasizing certain events, downplaying others, and interpreting the past in ways that support a particular ideological viewpoint.

Historians with conservative leanings might emphasize the importance of tradition and social order, while historians with liberal leanings might emphasize individual rights and social justice. This can lead to different interpretations of the same historical events.

Tools and Techniques of Revisionism

Historical revisionism employs a variety of tools and techniques to reshape the past. These methods are often subtle, making it challenging to identify and counter them. Understanding these tools is crucial for critically evaluating historical narratives and discerning the truth from manufactured accounts.

Propaganda and Historical Revisionism

Propaganda plays a significant role in rewriting history. It manipulates information to influence public opinion, often by distorting facts, omitting crucial details, and appealing to emotions.The following are common propaganda techniques used in historical revisionism:

- Name-calling: This technique uses negative labels to denigrate individuals or groups, fostering prejudice and animosity. For example, labeling political opponents as “traitors” or “enemies of the people” to discredit their actions and erase their contributions from historical narratives.

- Glittering generalities: This involves using vague, emotionally appealing words to create a positive image without providing concrete evidence. Terms like “freedom,” “justice,” and “progress” are frequently used to justify actions, even if those actions contradict the stated ideals.

- Bandwagon: This technique encourages people to accept a particular viewpoint by implying that everyone else does. Historical narratives can be altered to suggest widespread support for a particular ideology or leader, even if the reality was significantly different.

- Testimonial: This uses endorsements from respected figures to lend credibility to a claim. For example, quoting a celebrated scientist or artist out of context to support a historical revisionist’s argument, even if the person’s expertise is unrelated to the subject matter.

- Plain folks: This attempts to present leaders or ideologies as ordinary people to gain public trust. Images and narratives might be crafted to portray them as relatable, down-to-earth individuals, masking their true intentions or the historical impact of their actions.

- Card stacking: This involves selectively presenting facts to support a specific viewpoint while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. Revisionists might highlight positive aspects of a particular regime while ignoring human rights abuses or economic failures.

- Transfer: This uses symbols or images associated with something respected to transfer positive feelings to another. For example, using the national flag or a revered historical figure to legitimize a controversial policy or leader, even if their actions contradict the values represented by those symbols.

Source Selection and Manipulation

The selection and manipulation of historical sources are fundamental to revisionism. The choice of which sources to include, how they are interpreted, and what is omitted can dramatically alter historical accounts.

- Selective Use of Primary Sources: Revisionists may focus on specific primary sources that support their claims while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. For instance, a revisionist might emphasize documents that portray a historical figure favorably while omitting those that reveal their flaws or negative actions.

- Misinterpretation of Primary Sources: Primary sources can be deliberately misinterpreted to support a particular narrative. This might involve taking quotes out of context, altering translations, or imposing a modern interpretation on historical language and concepts.

- Reliance on Biased Secondary Sources: Revisionists often rely on secondary sources that align with their views, reinforcing their interpretations and providing a veneer of scholarly legitimacy. They might cite authors known for their controversial viewpoints or who have a vested interest in promoting a particular narrative.

- Fabrication of Sources: In extreme cases, historical revisionists might fabricate sources to support their claims. This can involve creating documents, altering existing ones, or presenting forgeries as authentic historical evidence.

- Suppression of Sources: Important primary sources might be suppressed or made inaccessible to prevent scrutiny of the revisionist narrative. This can involve governments or organizations controlling access to archives or deliberately misclassifying documents.

Education Systems and Revised Historical Narratives

Education systems play a crucial role in shaping historical understanding. They can either perpetuate revised narratives or challenge them.

- Curriculum Development: The content of history curricula can be manipulated to promote specific interpretations of the past. Textbooks, lesson plans, and teaching materials might emphasize certain events or perspectives while omitting others, thereby shaping students’ understanding of history.

- Teacher Training: Teachers’ training and professional development can influence how history is taught. Teachers who are not adequately trained to critically evaluate sources or recognize revisionist tactics may inadvertently perpetuate distorted historical narratives.

- Assessment Methods: Assessment methods, such as exams and essays, can reinforce or challenge revised narratives. Questions that favor specific interpretations or that discourage critical thinking can perpetuate biased historical accounts.

- Historical Monuments and Memorials: The construction and maintenance of historical monuments and memorials can contribute to or challenge revised historical narratives. These structures often present a specific interpretation of the past, reinforcing certain values and ideologies.

- Public Discourse: Education systems can promote critical thinking and encourage students to question established narratives. This can involve teaching students how to analyze sources, identify biases, and understand the complexities of historical events.

Case Studies: Examples of Rewritten History

Source: thetrumpet.com

Examining specific instances of historical revisionism provides concrete examples of how narratives are manipulated and the impact these revisions have. These case studies illuminate the methods used to alter historical accounts and the motivations behind these efforts. They highlight the importance of critical thinking and source evaluation when encountering historical information.

Rewriting the Holocaust

The Holocaust, a horrific event in human history, has been subject to various attempts at rewriting, primarily aimed at denial or minimizing its scope and impact. These revisions often involve distortion of facts, selective use of evidence, and the promotion of conspiracy theories.

- Denial of the Holocaust’s Existence: This involves outright claims that the Holocaust never happened. Deniers often assert that the evidence, such as eyewitness accounts, photographs, and documents, is fabricated or misinterpreted. They frequently dispute the existence of gas chambers and the systematic extermination of Jews.

- Minimization of Casualties: Another tactic is to acknowledge the Holocaust but drastically reduce the number of victims. Revisionists might claim that the number of deaths is exaggerated, often citing lower figures than the widely accepted estimate of six million Jews killed.

- Blaming the Victims: Some revisionists attempt to shift blame onto the victims themselves. This might involve claims that Jews provoked their own persecution or that they were responsible for the war.

- Distorting Historical Context: Revisionists often distort the historical context of the Holocaust by ignoring or downplaying the antisemitic ideologies and policies that led to the genocide. They may portray the Nazis as acting in self-defense or motivated by other factors.

- Promoting Conspiracy Theories: Conspiracy theories frequently accompany Holocaust denial, often claiming that the Holocaust was a hoax perpetrated by Jews to gain sympathy or financial advantage. These theories often target Jewish people and organizations, accusing them of controlling the media, governments, and financial institutions.

Comparing Narratives of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1917, a pivotal event in world history, has been subject to varying interpretations, each reflecting different ideological perspectives and political agendas. Comparing the official Soviet narrative with alternative interpretations reveals the complexities and contested nature of historical accounts.

- Official Soviet Narrative: The Soviet narrative portrayed the revolution as a triumph of the proletariat, a necessary and just overthrow of the oppressive Tsarist regime. It emphasized the role of the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, as the vanguard of the revolution, guiding the working class to liberation. The narrative celebrated the establishment of a socialist state and the eventual victory over capitalist enemies.

It often minimized or ignored the internal conflicts, repressions, and economic hardships that followed the revolution.

- Alternative Interpretations: Alternative interpretations challenge the official Soviet narrative in various ways. Some historians emphasize the role of other political groups, such as the Mensheviks or the Socialist Revolutionaries, in the revolution. They might highlight the spontaneous uprisings and popular movements that contributed to the collapse of the Tsarist regime, rather than focusing solely on the Bolsheviks’ actions. Other interpretations criticize the Bolsheviks’ authoritarianism and the violence that characterized the revolution and its aftermath.

They might also explore the social and economic consequences of the revolution, including the famines, purges, and the suppression of dissent.

- Focus on Specific Events:

- October Revolution: The official narrative celebrated the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917 as a heroic act. Alternative interpretations might depict it as a coup d’état, emphasizing the limited popular support for the Bolsheviks at the time.

- Russian Civil War: The Soviet narrative often framed the Civil War as a struggle against counter-revolutionaries and foreign intervention. Alternative interpretations might emphasize the brutality of the war, the suffering of the civilian population, and the complex motivations of the various factions involved.

- Stalin’s Purges: The official narrative, during Stalin’s era, often downplayed or justified the purges. Alternative interpretations highlight the scale of the repression, the targeting of innocent people, and the devastating impact on Soviet society.

Revising the American Civil War

The American Civil War, a defining event in U.S. history, has been subject to historical revisionism, particularly regarding its causes, the motivations of the participants, and the consequences of the conflict. The following blockquote presents diverse perspectives on the Civil War.

Perspective 1: The Confederate Perspective

The Confederate narrative often emphasized states’ rights and the defense of Southern way of life, including the institution of slavery, as the primary causes of the war. It frequently portrayed Confederate soldiers as heroes fighting for their independence against Northern aggression. This narrative often romanticized the antebellum South and downplayed the brutality of slavery.

Perspective 2: The Union Perspective

The Union perspective emphasized the preservation of the Union and the abolition of slavery as the primary goals of the war. It often portrayed the Confederacy as a rebellion against the legitimate authority of the United States. This narrative highlighted the moral imperative of ending slavery and the importance of national unity.

Perspective 3: The Economic and Social Perspective

This perspective examines the economic and social factors that contributed to the war, such as the competition between the industrial North and the agrarian South, and the impact of slavery on the Southern economy. It explores the experiences of various groups, including enslaved people, free blacks, and women, during the war.

Perspective 4: The Revisionist Perspective

Revisionist perspectives might challenge the traditional narratives, focusing on aspects often overlooked, such as the role of class conflict within the South, the motivations of individual soldiers, or the long-term consequences of the war on different regions and groups. Some revisionist historians examine the war from the perspective of marginalized communities, offering new insights into the causes, course, and impact of the conflict.

Impact and Consequences

Source: thetinkersmoon.com

Rewriting history, regardless of its motivation or method, leaves a significant mark on society. The consequences ripple outwards, affecting trust, international relations, and the very fabric of how we understand the past and present. Understanding these impacts is crucial for navigating the complexities of historical revisionism and its potential dangers.

Social Consequences of Rewriting History

Historical revisionism can erode societal trust in established institutions. When the past is manipulated, the reliability of information, including educational materials, news outlets, and government pronouncements, comes into question. This can lead to widespread skepticism and cynicism.

- Erosion of Trust in Institutions: When historical narratives are altered, it undermines the credibility of the institutions responsible for preserving and disseminating that history. This can include museums, universities, and government archives. For example, if a government systematically rewrites its role in a past conflict, citizens may lose faith in its current policies and pronouncements.

- Increased Social Polarization: Revisionist narratives often serve to divide rather than unite. By selectively highlighting certain aspects of the past and downplaying others, they can exacerbate existing social tensions and create new ones. This is particularly evident when revisionism is used to promote nationalist agendas or to demonize specific groups.

- Spread of Misinformation and Disinformation: Rewritten histories often rely on false or misleading information. This can contribute to the proliferation of conspiracy theories and other forms of misinformation. The internet and social media platforms can amplify these narratives, making it difficult for people to distinguish between fact and fiction.

- Impact on Education and Critical Thinking: When historical curricula are manipulated, students may not receive an accurate understanding of the past. This can hinder their ability to think critically, analyze information objectively, and make informed decisions. It can also lead to a lack of historical empathy and a diminished capacity for understanding diverse perspectives.

Impact of Historical Revisionism on International Relations and Conflicts

Historical revisionism frequently fuels international tensions and contributes to armed conflicts. When nations or groups rewrite history to support their political agendas, it can lead to misinterpretations of past events, justifying present-day actions and creating animosity between nations.

- Fueling Nationalist Agendas: Revisionist narratives are often used to promote nationalist agendas by glorifying a nation’s past, downplaying its negative aspects, and demonizing other nations or groups. This can lead to increased tensions and conflict. For instance, the revisionist claims about the origins of World War I continue to affect relations between various European nations.

- Justification for Territorial Claims: Rewriting history can be used to justify territorial claims or other expansionist policies. By manipulating historical narratives, governments can attempt to legitimize their actions and garner support from their populations. The ongoing disputes over the South China Sea, where historical claims are heavily contested, are a good example.

- Exacerbating Existing Conflicts: Historical revisionism can exacerbate existing conflicts by reinforcing negative stereotypes, promoting resentment, and undermining efforts at reconciliation. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a prime example, where competing historical narratives are used to justify opposing claims and actions.

- Undermining Diplomatic Efforts: When historical narratives are contested, it can be difficult to find common ground in diplomatic negotiations. Revisionist claims can undermine trust and make it harder to reach peaceful resolutions. The disputes surrounding the history of the Armenian genocide have, for example, complicated relations between Turkey and Armenia.

Challenges of Combating Historical Revisionism

Combating historical revisionism is a complex and multifaceted challenge. It requires a combination of educational efforts, critical thinking skills, and a commitment to historical accuracy. The following points highlight some of the key difficulties.

- Difficulty in Identifying and Addressing Revisionist Narratives: Revisionist narratives can be subtle and difficult to identify, especially when they are presented by trusted sources or when they align with existing biases. This requires a high degree of critical thinking and a willingness to question accepted narratives.

- Resistance to Change: People often resist changing their beliefs, especially when those beliefs are deeply rooted in their identity or sense of belonging. Challenging revisionist narratives can therefore be met with strong resistance. This is particularly true when the revisionism is tied to national identity or cultural heritage.

- The Spread of Misinformation: The internet and social media have made it easier than ever for misinformation and disinformation to spread. This can make it difficult to counter revisionist narratives, as they can quickly gain traction and reach a wide audience.

- Political and Ideological Polarization: Political and ideological polarization can make it difficult to have productive conversations about historical events. People on different sides of the political spectrum may be unwilling to engage with alternative perspectives or to acknowledge the validity of opposing viewpoints.

- Lack of Access to Reliable Sources: Access to reliable historical sources, such as primary documents and scholarly research, is essential for combating revisionism. However, such sources may be difficult to access or may be deliberately withheld or manipulated by those promoting revisionist narratives.

Countering Historical Revisionism

Combating historical revisionism requires a multifaceted approach. It involves equipping individuals with the skills to identify and critically evaluate potentially misleading historical narratives, promoting media literacy, and fostering a culture of rigorous historical analysis. This section explores practical strategies for effectively challenging false or distorted historical accounts.

Identifying and Evaluating Historical Revisionism

Detecting historical revisionism requires a keen eye and a systematic approach. Several key indicators can help distinguish between legitimate historical debate and attempts to manipulate the past.

- Scrutinizing Source Material: A cornerstone of identifying revisionism is evaluating the sources used. Be wary of accounts that rely heavily on biased sources, such as propaganda, unsubstantiated rumors, or documents with clear agendas. Always consider the origin, purpose, and potential biases of the source. Cross-referencing information with multiple independent sources is crucial.

- Analyzing Claims of Omission or Emphasis: Revisionist narratives often selectively present information, omitting facts that contradict their argument or overemphasizing certain aspects to create a skewed impression. Look for what is missing or downplayed, and consider why those elements might have been excluded. A balanced historical account should acknowledge multiple perspectives and address complexities.

- Recognizing the Use of Logical Fallacies: Revisionists frequently employ logical fallacies to persuade their audience. These can include appeals to emotion, straw man arguments (misrepresenting an opponent’s position), and ad hominem attacks (attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself). Familiarizing oneself with common logical fallacies is essential for identifying manipulative tactics.

- Assessing Contextual Accuracy: Historical events must be understood within their proper context. Revisionist accounts often distort or ignore the social, political, and economic conditions of the time. Ensure that the narrative aligns with the broader historical context and that claims are supported by evidence from the relevant period.

- Evaluating the Motivations of the Revisionist: Understanding the motivations behind a revisionist account can provide valuable insight into its potential biases. Consider the author’s background, affiliations, and any potential political or ideological agendas. This does not automatically invalidate their claims, but it helps to assess the credibility and potential biases of their work.

Critical Thinking and Media Literacy in Challenging False Narratives

Critical thinking and media literacy are indispensable tools in the fight against historical revisionism. They empower individuals to analyze information critically, recognize manipulative techniques, and resist the spread of misinformation.

- Developing Critical Thinking Skills: Critical thinking involves actively analyzing information, evaluating evidence, and forming reasoned judgments. This includes questioning assumptions, identifying biases, and considering alternative perspectives. Practice evaluating arguments, identifying logical fallacies, and recognizing the difference between fact and opinion.

- Cultivating Media Literacy: Media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media messages. This involves understanding how media is constructed, recognizing its potential biases, and identifying the techniques used to persuade and influence audiences. Become familiar with different types of media, their purposes, and their potential impacts.

- Cross-Referencing Information: Never rely on a single source. Verify information by consulting multiple reputable sources, including academic journals, historical archives, and credible news organizations. Look for corroborating evidence and be skeptical of claims that are not supported by multiple sources.

- Understanding Confirmation Bias: Be aware of confirmation bias, the tendency to seek out and interpret information that confirms pre-existing beliefs. Actively seek out diverse perspectives and be willing to challenge your own assumptions.

- Promoting Open Dialogue and Debate: Encourage respectful and informed discussions about historical events. Share your findings with others, and be open to different interpretations. Creating a culture of intellectual curiosity and critical inquiry is crucial for countering revisionism.

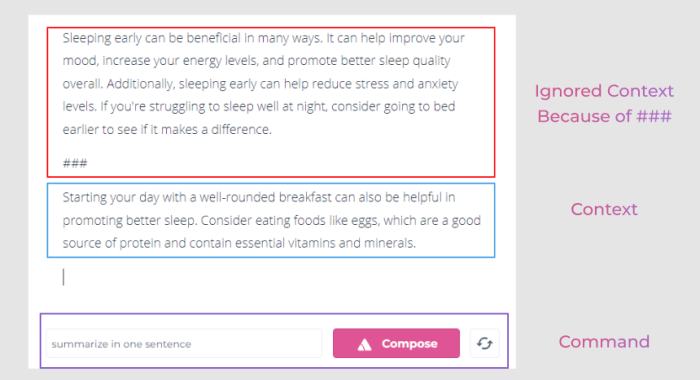

Components of Historical Analysis

Effective historical analysis relies on a structured approach to understanding the past. The following diagram illustrates the key components and their interrelationships.

Imagine an illustration depicting the components of historical analysis. The central element is a circle labeled “Historical Event.” Radiating outwards from this central circle are several interconnected components, each represented by a smaller circle or shape.

- Primary Sources: A circle on the left side of the diagram contains icons representing letters, a diary, a photograph, and a government document. This circle is labeled “Primary Sources.” Arrows point from the “Primary Sources” circle towards the “Historical Event” circle, signifying that primary sources provide direct evidence about the event.

- Secondary Sources: A circle on the right side of the diagram shows icons of books, articles, and textbooks. This is labeled “Secondary Sources.” Arrows point from “Secondary Sources” towards “Historical Event,” indicating that secondary sources offer interpretations and analyses of the event, based on primary sources.

- Contextual Factors: Above the “Historical Event” circle, a shape contains icons symbolizing political structures, economic systems, social norms, and cultural beliefs. This is labeled “Contextual Factors.” Arrows point from this shape to “Historical Event,” highlighting the importance of understanding the surrounding circumstances.

- Analysis and Interpretation: Below the “Historical Event” circle, a circle depicts a magnifying glass, a question mark, and a lightbulb. This is labeled “Analysis and Interpretation.” Arrows point from the “Historical Event” circle towards “Analysis and Interpretation,” indicating that the event is subject to critical examination.

- Bias and Perspective: Surrounding the entire diagram, a cloud-like shape contains icons representing various viewpoints, personal beliefs, and cultural backgrounds. This is labeled “Bias and Perspective.” Arrows connect this shape to all other components, indicating that bias can influence source selection, contextual understanding, and analysis.

This interconnected diagram shows that understanding history requires examining primary and secondary sources within a specific context, considering potential biases, and conducting thorough analysis and interpretation.

Closure

In conclusion, rewriting history is a multifaceted issue with significant implications for society, international relations, and individual understanding. From the motivations driving it to the techniques used, and the tools available, this exploration aims to equip readers with the critical thinking skills needed to navigate the complexities of historical narratives. By understanding the forces at play, we can work towards a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the past, fostering a more informed and just future.

Popular Questions

What is the difference between historical revisionism and historical interpretation?

Historical interpretation involves analyzing the past based on available evidence and may offer new perspectives, while historical revisionism deliberately alters facts or presents a biased narrative to serve a specific agenda.

How can I identify historical revisionism?

Look for narratives that selectively use evidence, omit crucial information, or present a biased viewpoint. Check multiple sources, be aware of the author’s potential biases, and verify facts with credible sources.

Is all historical revisionism inherently negative?

Not necessarily. Some revisions can offer fresh perspectives or correct past errors. However, revisionism becomes problematic when it intentionally distorts the past for political, ideological, or personal gain.

What role does education play in combating historical revisionism?

Education is crucial. Teaching critical thinking skills, media literacy, and providing access to diverse historical perspectives can empower individuals to identify and challenge false narratives.

How does propaganda contribute to rewriting history?

Propaganda uses biased information, misinformation, and emotional appeals to manipulate public opinion and rewrite historical events to support a particular ideology or agenda.