Dive into the fascinating world of the Atlantic Rift, a colossal underwater mountain range that’s constantly reshaping our planet. This geological marvel, also known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, is where the Earth’s tectonic plates are slowly pulling apart, creating a dynamic and awe-inspiring landscape beneath the waves. From fiery volcanoes to unique ecosystems teeming with life, the Atlantic Rift is a treasure trove of geological wonders and scientific discoveries.

The Atlantic Rift isn’t just a geographical feature; it’s a window into the inner workings of our planet. It’s where new oceanic crust is born, fueling the ongoing process of plate tectonics. This process has shaped the continents and oceans over millions of years and continues to do so today. Understanding the Atlantic Rift is key to understanding Earth’s past, present, and future.

Introduction to the Atlantic Rift

Source: britannica.com

The Atlantic Rift, a fundamental geological feature, plays a crucial role in shaping our planet. It represents a significant area of active geological processes, offering valuable insights into the dynamics of plate tectonics and the ongoing evolution of Earth’s surface. Understanding the Atlantic Rift is key to grasping the formation of the Atlantic Ocean and the broader implications of continental drift.

Rift Valley Formation

Rift valleys are formed through the process of continental rifting, which is the stretching and thinning of the Earth’s lithosphere. This process typically begins with the upwelling of hot mantle material beneath a continental plate. This causes the crust to dome upwards and experience extensional forces, leading to the formation of normal faults. These faults allow blocks of crust to subside, creating a valley-like depression known as a rift valley.

Over millions of years, if rifting continues, the continental crust can break apart, and a new ocean basin can form. The Atlantic Ocean is a prime example of an ocean formed by this process.

Mid-Atlantic Ridge Location

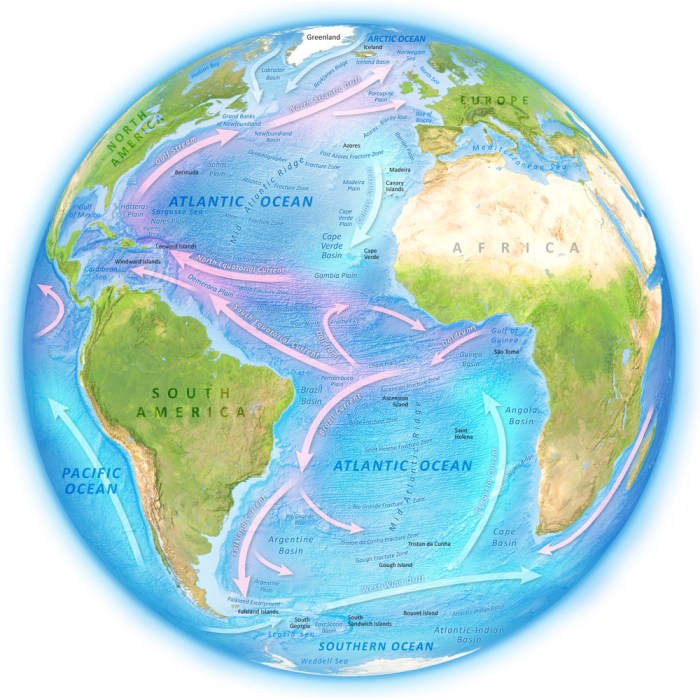

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a massive underwater mountain range that runs down the center of the Atlantic Ocean. It is a divergent plate boundary, where the North American and Eurasian plates, and the South American and African plates, are moving apart. This ridge extends for over 65,000 kilometers (40,000 miles), making it the longest mountain range on Earth. The ridge is characterized by volcanic activity and frequent earthquakes, as molten rock from the mantle rises to the surface, creating new oceanic crust.

Significance in Plate Tectonics

The Atlantic Rift is of immense significance in plate tectonics, serving as a primary site of seafloor spreading. It provides direct evidence of how tectonic plates move and interact. The continuous formation of new oceanic crust at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, through volcanic eruptions and the cooling of magma, is a fundamental process driving plate tectonics. This process causes the older oceanic crust to be pushed away from the ridge, ultimately being subducted (pushed under) at convergent plate boundaries elsewhere on the globe.The Atlantic Rift offers a valuable model for understanding the evolution of ocean basins and the broader implications of plate tectonics.

The study of this area has provided important data, such as:

- Seafloor Spreading Rates: By analyzing the magnetic anomalies in the ocean floor, scientists can determine the rate at which the seafloor is spreading. This data has confirmed the theory of plate tectonics. For instance, the spreading rate varies along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, with some sections spreading faster than others.

- Volcanic Activity: The frequent volcanic eruptions along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge contribute to the creation of new oceanic crust. These eruptions provide insights into the composition of the Earth’s mantle and the processes involved in magma formation.

- Earthquake Activity: The Atlantic Rift is prone to earthquakes, which occur as a result of the movement of tectonic plates. Studying these earthquakes helps scientists understand the stresses and strains within the Earth’s crust.

The rate of seafloor spreading can be estimated using the formula:

Rate = Distance / Time

Formation and Development of the Atlantic Rift

Source: worldatlas.com

The Atlantic Ocean, a vast expanse of water separating continents, wasn’t always here. Its formation is a dynamic story of geological processes, spanning hundreds of millions of years. This section delves into the forces that ripped apart the supercontinent Pangaea and the subsequent evolution of the Atlantic, from its nascent rifts to its current state.

Initial Rifting of Pangaea

The breakup of Pangaea, the supercontinent that existed roughly 335 to 175 million years ago, was a complex process driven primarily by plate tectonics. This involved the movement and interaction of Earth’s lithospheric plates, the rigid outer shell of the planet.The initial rifting began with the stretching and thinning of the Earth’s crust. This process, known as continental rifting, is characterized by:

- Tensional Forces: These forces pull the crust apart. This stretching causes the lithosphere to thin, creating zones of weakness.

- Faulting and Subsidence: As the crust thins, it fractures along faults. These faults create rift valleys, which are long, narrow depressions in the Earth’s surface. These valleys then subside, meaning they sink lower relative to the surrounding land.

- Volcanic Activity: The thinning crust allows magma from the mantle to rise to the surface. This leads to volcanic eruptions and the formation of volcanic rocks within the rift valleys.

This initial rifting phase was marked by the formation of grabens (down-dropped blocks of crust) and horsts (uplifted blocks). These features are characteristic of continental rifting environments. As rifting progressed, the continental crust eventually broke apart, leading to the formation of a new ocean basin. An example of a modern-day rift valley in an early stage of development is the East African Rift Valley.

Role of Mantle Plumes

Mantle plumes, upwellings of hot rock from deep within the Earth’s mantle, played a significant role in the breakup of Pangaea and the formation of the Atlantic Rift. These plumes, characterized by their high temperatures, rise towards the Earth’s surface and can cause significant geological activity.Mantle plumes influence rifting in several ways:

- Crustal Uplift: When a mantle plume approaches the base of the lithosphere, it causes the overlying crust to bulge upwards. This uplift creates a dome-like structure, which can then be subject to tensional stresses, initiating rifting.

- Volcanic Activity: Mantle plumes are a source of significant heat and magma. As the crust thins during rifting, magma from the plume can erupt onto the surface, forming extensive flood basalts. The North Atlantic Igneous Province (NAIP), a large igneous province formed around the time the North Atlantic began to open, provides a good example of this phenomenon.

- Weakening of the Lithosphere: The heat from mantle plumes weakens the lithosphere, making it more susceptible to rifting. This weakening facilitates the stretching and breaking of the continental crust.

The Iceland hotspot, located beneath the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, is a prime example of a mantle plume influencing the formation and evolution of an ocean basin. This hotspot continues to supply magma to the ridge, contributing to Iceland’s volcanic activity and the ongoing widening of the Atlantic.

Chronological Sequence of the Atlantic Ocean’s Opening

The opening of the Atlantic Ocean was a gradual process, unfolding over millions of years. This sequence Artikels the major stages:

- Late Triassic Period (around 200 million years ago): Initial rifting began. The supercontinent Pangaea started to break apart. Rift valleys formed, and volcanic activity increased. The Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) experienced massive flood basalt eruptions.

- Early Jurassic Period (around 180 million years ago): The rifting intensified. The North Atlantic began to open between North America and Eurasia. The South Atlantic began to open between South America and Africa. The initial oceanic crust began to form.

- Mid-Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Periods (around 160-120 million years ago): The Atlantic Ocean continued to widen. The formation of new oceanic crust continued along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The continents began to drift further apart.

- Late Cretaceous Period (around 100-66 million years ago): The Atlantic Ocean continued to expand. The South Atlantic widened significantly. The continents assumed shapes more similar to their present-day configurations.

- Cenozoic Era (66 million years ago to present): The Atlantic Ocean continued to widen. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge continues to generate new oceanic crust. The continents gradually moved to their current positions. The Atlantic Ocean continues to evolve.

The Atlantic Ocean’s ongoing expansion is a direct result of seafloor spreading, a process driven by the convection currents in the Earth’s mantle. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a prominent underwater mountain range, is where new oceanic crust is constantly being created. The rate of seafloor spreading varies across the Atlantic, but on average, the ocean is widening by a few centimeters each year.

Geological Features of the Atlantic Rift

The Atlantic Rift, specifically the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, is a dynamic geological feature characterized by a variety of formations and processes. These features provide valuable insights into plate tectonics, seafloor spreading, and the Earth’s internal processes. Studying these features helps us understand how the Atlantic Ocean is formed and how it continues to evolve.

Key Geological Features of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is not a single, continuous mountain range; it’s a complex system of interconnected features. Several key geological structures are associated with this ridge, each playing a crucial role in its formation and ongoing activity.

- Transform Faults: These are fracture zones where plates slide horizontally past each other. They are common along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, offsetting the spreading axis. The movement along these faults can generate earthquakes. An example is the Romanche Fracture Zone, one of the longest transform faults in the Atlantic, which offsets the Mid-Atlantic Ridge by hundreds of kilometers.

- Seamounts: These are underwater mountains formed by volcanic activity. They rise from the seafloor but do not reach the surface to become islands (though some can). Seamounts are abundant along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, formed by the eruption of lava from the mantle. The Canary Islands Seamount Province is a well-known area in the Atlantic Ocean with numerous seamounts, showcasing the volcanic activity associated with the region.

- Hydrothermal Vents: These are fissures in the seafloor that release geothermally heated water. The water is often rich in dissolved minerals, which precipitate out, forming chimneys and supporting unique ecosystems. These vents, often called “black smokers” or “white smokers” based on the color of the mineral-rich water they emit, are home to extremophile organisms that thrive in the harsh conditions. For example, the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, located on the Atlantis Massif, is a remarkable example of a vent system that releases alkaline fluids, supporting a distinct biological community.

Volcanic Activity Along the Ridge

Volcanic activity is the driving force behind the formation and evolution of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The ridge is characterized by several types of volcanic activity, primarily associated with the upwelling of magma from the Earth’s mantle.

- Fissure Eruptions: These eruptions involve the release of lava from long fissures or cracks in the Earth’s crust. They are the most common type of volcanic activity along the ridge, responsible for building the vast stretches of the seafloor. These eruptions typically produce basaltic lava flows, which spread out over large areas.

- Shield Volcanoes: These are broad, gently sloping volcanoes formed by the eruption of low-viscosity lava. While not as prominent as fissure eruptions, shield volcanoes are also found along the ridge. They contribute to the overall height and width of the ridge.

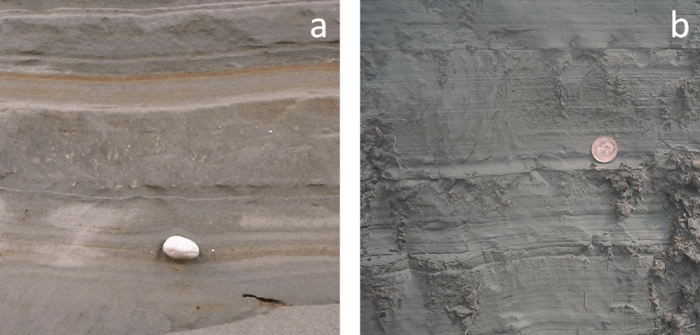

- Pillow Lavas: These are distinctive formations of lava that erupt underwater. The lava quickly cools upon contact with the water, forming rounded, pillow-like structures. Pillow lavas are a clear indicator of submarine volcanic activity.

Formation of Rock Types in the Rift Zone

The rock types found in the rift zone provide a record of the geological processes occurring there. These rocks are formed through various processes, each leaving its mark on the composition and characteristics of the material.

| Rock Type | Formation Process | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Basalt | Crystallization of rapidly cooled lava, typically from fissure eruptions. | Fine-grained, dark-colored, rich in iron and magnesium. Forms the majority of the oceanic crust. |

| Gabbro | Slow cooling and crystallization of magma deep within the crust. | Coarse-grained, dark-colored, with visible crystals of plagioclase and pyroxene. Represents the solidified magma chambers beneath the ridge. |

| Peridotite | Partially molten mantle material that rises to the surface. | Coarse-grained, green or dark-colored, rich in olivine and pyroxene. Represents the mantle material exposed at the ridge. |

| Hydrothermal Vent Deposits | Precipitation of minerals from hydrothermal fluids. | Variable composition, often including sulfides (e.g., pyrite, chalcopyrite), sulfates, and oxides. Forms chimneys and mounds around vents. |

Volcanic and Seismic Activity in the Atlantic Rift

The Atlantic Rift, a dynamic zone of geological activity, is characterized by significant volcanic and seismic events. These phenomena are directly linked to the processes of plate tectonics, where the Earth’s crustal plates move, interact, and create the conditions for eruptions and earthquakes. This activity shapes the ocean floor and influences the surrounding environments.

Plate Movement and Volcanic Eruptions

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the most prominent feature of the Atlantic Rift, is a divergent plate boundary. Here, the North American and Eurasian plates, and the South American and African plates, are moving apart. This separation allows magma from the Earth’s mantle to rise and erupt onto the ocean floor, creating new crust.The relationship between plate movement and volcanic eruptions can be summarized as follows:

- As plates move apart, the lithosphere thins, reducing pressure on the underlying mantle.

- This pressure reduction causes the mantle rock to melt, forming magma.

- The magma, being less dense than the surrounding rock, rises through cracks and fissures in the crust.

- The magma erupts as lava onto the ocean floor, building up underwater volcanoes.

- These eruptions continually add new material to the oceanic crust, driving the process of seafloor spreading.

An example of this process is evident near Iceland, where the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is exposed above sea level. The island nation is a result of the constant volcanic activity along the ridge, creating a landmass composed of basaltic lava flows. The frequency of eruptions varies, but they are a constant feature of the landscape, directly linked to the ongoing separation of the Eurasian and North American plates.

The most recent significant eruption, the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption, demonstrated the continued volcanic activity. This eruption produced significant lava flows, illustrating the ongoing process of crust formation.

Frequency and Intensity of Earthquakes

The Atlantic Rift is also a seismically active zone, experiencing numerous earthquakes due to the stresses associated with plate movement. These earthquakes are primarily shallow-focus earthquakes, occurring near the plate boundary.The frequency and intensity of earthquakes in the rift zone are influenced by several factors:

- The rate of plate separation: Faster spreading rates can lead to more frequent, though not necessarily more intense, seismic activity.

- The presence of transform faults: These faults, which run perpendicular to the ridge, can experience significant strike-slip motion, generating moderate to large earthquakes.

- The build-up and release of stress along the plate boundary: Over time, stress accumulates, eventually leading to sudden releases of energy in the form of earthquakes.

Earthquakes in the Atlantic Rift are generally less intense than those found in subduction zones like the Pacific Ring of Fire. However, they still pose a hazard. Data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) shows that thousands of earthquakes occur annually along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. While most are small, some can reach magnitudes of 6 or 7 on the Richter scale, capable of causing localized damage.

For instance, the 1997 earthquake near the Azores Islands, with a magnitude of 6.2, caused damage to infrastructure.

Potential Hazards

Volcanic and seismic activity in the Atlantic Rift poses several potential hazards. While the remote location of much of the activity reduces the direct impact on human populations, these hazards still exist.The potential hazards associated with volcanic and seismic activity include:

- Volcanic Eruptions: Underwater eruptions can generate large volumes of lava, potentially disrupting marine ecosystems. In some cases, explosive eruptions can generate ash clouds that may affect air travel.

- Earthquakes: Earthquakes can trigger tsunamis, particularly if they occur near the coast or involve significant vertical displacement of the seafloor. Ground shaking can also damage underwater infrastructure, such as communication cables.

- Tsunamis: Although less frequent than in subduction zones, tsunamis generated by earthquakes or underwater landslides pose a risk to coastal communities. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, although not directly related to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, serves as a historical example of the devastating impact a large earthquake and subsequent tsunami can have on coastal populations.

- Hydrothermal Vent Activity: Volcanic activity is often associated with hydrothermal vents, which release hot, mineral-rich fluids into the ocean. While these vents support unique ecosystems, they can also release toxic substances into the water.

Understanding these hazards and monitoring volcanic and seismic activity is crucial for mitigating potential risks and protecting both the environment and human interests. The development of early warning systems and improved monitoring techniques are essential for enhancing preparedness and response capabilities in the Atlantic Rift region.

Hydrothermal Vents and Unique Ecosystems

Source: co.uk

The Atlantic Rift, a dynamic zone of geological activity, is not only a site of tectonic plate movement but also a fascinating habitat for life. Deep within its fissures, where the Earth’s crust is thin and volcanic activity is prevalent, unique ecosystems thrive around hydrothermal vents. These vents, essentially underwater hot springs, support life in ways that are entirely independent of sunlight, representing some of the most extreme and intriguing environments on Earth.

Hydrothermal Vent Formation

Hydrothermal vents are formed through a complex interplay of geological processes. Cold seawater seeps into the Earth’s crust through cracks and fissures along the rift. As this water descends, it encounters hot magma and volcanic rocks, causing it to heat up significantly. This superheated water dissolves minerals from the surrounding rocks. The heated, mineral-rich water then rises back up through the crust, often through chimney-like structures, and is expelled into the surrounding cold ocean water.

Unique Organisms in Extreme Environments

The extreme conditions around hydrothermal vents, including high temperatures, toxic chemicals, and intense pressure, have led to the evolution of unique organisms. These creatures have adapted to survive in environments that would be lethal to most life forms.

- Giant Tube Worms: These iconic vent inhabitants lack a digestive system and rely on symbiotic bacteria for nutrition. They have a bright red plume that absorbs chemicals from the vent water, which the bacteria use to produce food through chemosynthesis. They can grow to over 2 meters in length.

- Giant Clams: Similar to tube worms, giant clams harbor chemosynthetic bacteria in their gills. They filter water and absorb nutrients, including those produced by the bacteria. They can reach impressive sizes, with shells exceeding a meter in length.

- Various Species of Shrimp and Crabs: Many species of shrimp and crabs, some of which are found nowhere else, are also commonly found around vents. They feed on bacteria, smaller organisms, or scavenge on dead organic matter. Some shrimp have specialized organs that can detect chemicals emitted by the vents.

- Specialized Fish: Some fish species, like the vent fish, have adapted to the high temperatures and toxic conditions near the vents. They often have unique physiological adaptations that allow them to thrive in this environment.

Chemosynthetic Processes Supporting Life

The foundation of the hydrothermal vent ecosystem is chemosynthesis, a process by which organisms use chemical energy to produce food. This is in contrast to photosynthesis, which uses sunlight. In the vent environment, bacteria utilize chemicals released from the vents, such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), to produce organic compounds.

H₂S + O₂ + CO₂ → Organic compounds + Sulfur

The above formula is a simplified representation of chemosynthesis, where hydrogen sulfide reacts with oxygen and carbon dioxide to produce organic compounds and sulfur. The bacteria perform this chemical reaction. These chemosynthetic bacteria form the base of the food web, supporting the diverse array of organisms that inhabit the vent communities. This process enables life to flourish in the deep ocean, far from the reach of sunlight, creating a remarkable and self-sustaining ecosystem.

The Atlantic Rift and Plate Tectonics

The Atlantic Rift is a textbook example of how plate tectonics shapes our planet. It’s a dynamic zone where the Earth’s crust is actively being created, constantly reshaping the ocean floor and influencing global geological processes. Understanding the Atlantic Rift provides crucial insights into the fundamental principles of plate tectonics.

Comparing Plate Movement Rates

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the underwater mountain range that forms the Atlantic Rift, isn’t a single, uniform feature. Different segments of the ridge exhibit varying rates of plate separation. These differences are influenced by factors like the composition of the mantle beneath the ridge and the presence of transform faults that accommodate differential movement.The rates of plate movement are generally slow, but vary significantly.

For instance, the northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge, near Iceland, is characterized by relatively faster spreading rates, averaging around 2.5 centimeters per year. In contrast, sections of the southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge, like those near the Bouvet Triple Junction, experience slower spreading rates, closer to 1 to 1.5 centimeters per year. These rates are determined using a variety of methods, including GPS measurements, analysis of magnetic anomalies in the seafloor, and the dating of volcanic rocks.

The faster spreading in Iceland contributes to a greater volume of volcanic activity and a wider ridge, while the slower spreading in the South Atlantic results in a narrower ridge with less frequent volcanism.

Forces Driving Plate Separation

The separation of plates in the Atlantic Rift is driven by a complex interplay of forces. These forces include:

- Mantle Convection: This is a primary driver. Hotter, less dense material from the Earth’s mantle rises towards the surface, creating upwelling currents beneath the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This upwelling pushes the plates apart.

- Ridge Push: As new crust is formed at the ridge, it is initially hot and less dense. As it moves away from the ridge, it cools and becomes denser, causing it to slide down the elevated ridge flanks under the force of gravity.

- Slab Pull: At subduction zones (which are not present in the Atlantic Rift, but are relevant to the overall plate tectonic process), the older, denser oceanic crust sinks back into the mantle, pulling the rest of the plate along with it. While not directly applicable to the Atlantic, the absence of this force contributes to the slower spreading rates observed in some parts of the Atlantic.

A simplified diagram illustrating these forces would depict:

A cross-section of the Earth, showing the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at the center. The diagram would depict the following elements:

1. Mantle Convection

Arrows would indicate the upwelling of hot, less dense mantle material beneath the ridge.

2. Ridge Push

Arrows would show the newly formed crust sliding down the flanks of the ridge under the influence of gravity.

3. Plates separating

Arrows would show the plates moving away from the ridge.

4. Magma chamber

A region of molten rock beneath the ridge, feeding the volcanic activity.

This diagram effectively illustrates the dynamic processes that shape the Atlantic Rift and drive plate separation.

The Atlantic Rift as a Divergent Plate Boundary

The Atlantic Rift is a classic example of a divergent plate boundary. At these boundaries, two tectonic plates move apart, allowing magma from the Earth’s mantle to rise and solidify, creating new oceanic crust. This process, known as seafloor spreading, is the defining characteristic of a divergent boundary.The creation of the Atlantic Ocean itself is a direct result of this divergent process.

Millions of years ago, the supercontinent Pangaea began to break apart, with the formation of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge as the initial rift zone. As the plates continued to diverge, the rift expanded, and the Atlantic Ocean basin gradually filled with water. Today, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge continues to generate new oceanic crust, widening the Atlantic Ocean by a few centimeters each year.

This makes the Atlantic Rift a continuously evolving system, demonstrating the ongoing nature of plate tectonics.

Resources and Exploration in the Atlantic Rift

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, while primarily known for its geological activity, also holds potential for valuable resources. Exploring this deep-sea environment presents significant challenges, but advancements in technology and scientific research are constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. Understanding the resources available and the methods used to explore them is crucial for responsible management and scientific advancement.

Potential Mineral Resources Near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The hydrothermal vent systems associated with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge are hotspots for mineral formation. These vents, where superheated water rich in dissolved minerals spews out from the Earth’s crust, create unique environments where valuable resources can precipitate.

- Polymetallic Sulfides: These are the most commonly discussed resources. They contain valuable metals like copper, zinc, gold, and silver. The formation occurs when the hot vent fluids mix with the cold seawater, causing the dissolved minerals to solidify and accumulate around the vent structures, creating chimney-like formations. These deposits are of interest for their economic potential. An example of this is the TAG (Trans-Atlantic Geotraverse) hydrothermal field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which has significant sulfide deposits.

- Cobalt-Rich Crusts: Found on seamounts and other hard surfaces near the ridge, these crusts can contain significant amounts of cobalt, along with other metals like manganese, nickel, and platinum. These crusts form through the slow precipitation of metals from seawater over millions of years. These are important for battery production and other industrial applications.

- Manganese Nodules: Although less prevalent in the Atlantic compared to the Pacific, manganese nodules can still be found. These potato-sized concretions contain manganese, iron, nickel, copper, and cobalt. The formation of these nodules is a slow process involving the precipitation of metals from seawater.

Challenges and Methods Used in Deep-Sea Exploration

Exploring the deep-sea environment of the Atlantic Rift presents significant logistical and technological hurdles. The immense pressure, darkness, and corrosive seawater necessitate specialized equipment and techniques.

- Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs): These are tethered robots controlled from a surface vessel. They are equipped with cameras, lights, and manipulators to collect samples and conduct detailed surveys. ROVs are the workhorses of deep-sea exploration, allowing scientists to access and study areas that are too deep or dangerous for human divers. An example is the ROV Jason, used extensively by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): These untethered robots operate independently, following pre-programmed missions. They can map the seafloor, collect data, and take high-resolution images. AUVs offer greater range and maneuverability than ROVs, allowing for more extensive surveys. The use of AUVs provides detailed bathymetric maps, revealing the complex topography of the rift zone.

- Submersibles: Manned submersibles, like the Alvin submersible, allow scientists to directly observe and sample the deep-sea environment. They offer a unique perspective and the ability to conduct hands-on research. Submersibles are limited by their depth rating and the duration of their missions. Alvin, for example, has played a key role in discoveries at hydrothermal vents.

- Hydroacoustic Surveys: These surveys use sonar technology to map the seafloor, detect hydrothermal plumes, and identify potential mineral deposits. This method allows for large-scale assessments of the rift zone. Side-scan sonar is often used to create detailed images of the seafloor, while multibeam sonar provides bathymetric data.

- Drilling and Coring: Specialized drilling equipment is used to collect samples of the seafloor sediments and rock formations. This provides valuable information about the geological history and the presence of mineral resources. The International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) uses research vessels equipped with drilling capabilities to collect core samples from the deep sea.

Scientific Research Conducted in the Atlantic Rift

The Atlantic Rift is a prime location for scientific research, attracting researchers from around the world. The study of the rift provides valuable insights into plate tectonics, hydrothermal vent ecosystems, and the formation of mineral deposits.

- Geological Studies: Scientists study the structure and composition of the oceanic crust, the processes of seafloor spreading, and the formation of volcanic features. Research focuses on understanding the movement of tectonic plates and the forces that drive them. Studies often involve seismic surveys and the analysis of rock samples.

- Hydrothermal Vent Research: The unique ecosystems around hydrothermal vents are a major focus of research. Scientists study the organisms that thrive in these extreme environments, their adaptations, and the role of chemosynthesis. The discovery of novel species and the study of their metabolic processes provide insights into the limits of life.

- Oceanographic Studies: The rift zone influences ocean currents, water chemistry, and the distribution of marine life. Research includes monitoring water temperature, salinity, and the transport of heat and chemicals. The study of the interplay between the rift and the surrounding ocean is essential for understanding the global climate system.

- Geochemical Analysis: Scientists analyze the chemical composition of seawater, hydrothermal fluids, and rock samples to understand the processes of magma generation, the formation of mineral deposits, and the cycling of elements in the ocean. The analysis of trace elements can provide insights into the origin of hydrothermal fluids and the sources of the metals.

The Future of the Atlantic Rift

The Atlantic Rift, a dynamic and ever-changing geological feature, holds clues to the planet’s past and hints at its future. Understanding its evolution is crucial for predicting the long-term changes impacting our planet. The following sections will explore the projected future of the Atlantic Ocean, the potential consequences of continued rifting on coastal regions, and the broader implications for global climate patterns.

Predicted Evolution of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is destined to continue its expansion, a process driven by the ongoing rifting along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This slow but relentless separation of tectonic plates will reshape coastlines and influence global ocean currents.

- Continued Widening: The Atlantic Ocean is growing wider at a rate of a few centimeters per year. This expansion is not uniform; some sections of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge are spreading faster than others. For example, the North Atlantic is generally spreading faster than the South Atlantic. This expansion will continue for millions of years.

- Formation of New Oceanic Crust: As the tectonic plates diverge, magma from the Earth’s mantle rises to fill the gap, solidifying to create new oceanic crust. This process, known as seafloor spreading, is the fundamental mechanism driving the Atlantic’s growth. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a prime example of this process in action, constantly producing new crust.

- Continental Drift and Coastal Changes: Over vast timescales, the continents bordering the Atlantic will drift further apart. North America and Europe, for instance, will continue to move away from each other. This movement will lead to gradual changes in coastal geography, potentially creating new islands and altering the shape of existing continents.

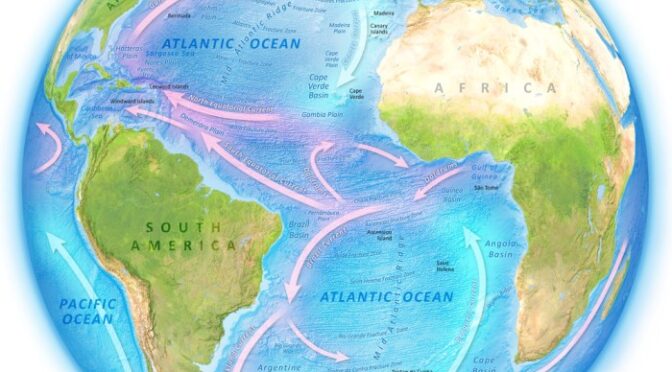

- Oceanic Current Modifications: The widening of the Atlantic will influence ocean currents. Changes in the shape and size of the ocean basin can affect the flow of major currents like the Gulf Stream, which plays a critical role in regulating regional climates. Alterations in these currents can have cascading effects on weather patterns globally.

Potential Effects of Continued Rifting on Coastal Regions

The ongoing rifting and subsequent continental drift pose several potential challenges and changes for coastal regions around the Atlantic. These effects include increased seismic activity, altered sea levels, and shifts in coastal morphology.

- Increased Seismic Activity: As tectonic plates continue to move, the stress built up at plate boundaries can lead to earthquakes. While the Mid-Atlantic Ridge itself is not typically associated with large, devastating earthquakes, the areas surrounding it, particularly near transform faults, may experience increased seismic activity. This could potentially affect coastal infrastructure and populations.

- Sea Level Changes: The overall expansion of the Atlantic, coupled with potential shifts in ocean basin volume due to tectonic activity, can indirectly influence sea levels. Furthermore, the thermal expansion of seawater due to climate change will add to this. These changes can exacerbate coastal erosion and increase the risk of flooding in low-lying areas.

- Coastal Erosion and Landform Alterations: Continued rifting and plate movement can alter coastal landforms over long periods. Changes in sea level, combined with tectonic uplift or subsidence, can accelerate erosion in some areas and lead to the formation of new land features, such as barrier islands or lagoons, in others. The long-term impact is a dynamic reshaping of coastal zones.

- Volcanic Activity: The rifting process is associated with volcanic activity. While most of the volcanic activity occurs underwater, it can still influence coastal regions. Volcanic eruptions can form new islands, alter coastal landscapes through lava flows, and impact water quality due to the release of volcanic gases and ash. The Canary Islands and Iceland are prime examples of volcanic activity associated with the Atlantic rift.

Long-Term Implications of the Atlantic Rift’s Development on Global Climate Patterns

The development of the Atlantic Rift has significant implications for global climate patterns. The ocean’s size, shape, and circulation patterns directly influence weather systems and the distribution of heat around the planet.

- Ocean Current Disruptions: The Atlantic Ocean’s circulation, driven by currents like the Gulf Stream, is a major factor in regulating global climate. Changes in the shape and size of the Atlantic basin, due to rifting, can disrupt these currents. For example, a weakening or shifting of the Gulf Stream could lead to significant cooling in Western Europe, as less warm water is transported northward.

- Heat Distribution Alterations: The Atlantic Ocean plays a crucial role in redistributing heat from the equator towards the poles. Changes in its size and shape can alter this heat distribution, leading to regional climate shifts. A broader Atlantic, for example, could potentially lead to more efficient heat transfer and affect temperature gradients across the globe.

- Impact on Atmospheric Circulation: The ocean’s influence extends to atmospheric circulation. Changes in sea surface temperatures, driven by alterations in ocean currents and heat distribution, can affect wind patterns and the formation of storms. This can lead to changes in precipitation patterns, impacting agriculture and water resources in various regions.

- Feedback Loops and Climate Amplification: The development of the Atlantic Rift can initiate or amplify climate feedback loops. For instance, changes in ocean circulation can affect the absorption of carbon dioxide by the ocean, impacting atmospheric CO2 levels and contributing to climate change. The melting of polar ice caps, influenced by ocean temperatures, can further accelerate sea-level rise and impact coastal regions.

Comparison with Other Rift Zones

Comparing the Atlantic Rift to other major rift zones provides valuable insights into the diverse processes shaping Earth’s surface. These comparisons highlight similarities and differences in tectonic settings, geological features, and ongoing activity. Examining these variations helps us understand the complex dynamics of plate tectonics and the evolution of our planet.

East African Rift: A Young, Active Rift

The East African Rift is a prime example of an active continental rift zone. This region showcases the early stages of continental breakup, offering a glimpse into the processes that formed the Atlantic Rift millions of years ago. The East African Rift is characterized by significant volcanic activity, earthquakes, and the formation of deep rift valleys.

- Plate Boundary Type: Divergent.

- Key Features:

- Rift valleys: Deep, linear depressions formed by crustal extension.

- Volcanoes: Active volcanoes like Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru.

- Faults: Numerous normal faults, creating a complex fault network.

- High heat flow: Indicative of underlying mantle activity.

- Lakes: Formation of large lakes like Lake Tanganyika and Lake Malawi.

- Current Activity: Ongoing extension, frequent earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. The region is experiencing significant crustal thinning and is in the process of continental rifting, which may eventually lead to the formation of a new ocean basin.

Mid-Atlantic Ridge: A Submarine Rift

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge represents a well-developed oceanic rift zone. This underwater mountain range stretches across the Atlantic Ocean and is a prime example of seafloor spreading. It’s where the North American and Eurasian plates, and the South American and African plates, are separating.

- Plate Boundary Type: Divergent.

- Key Features:

- Underwater mountain range: A continuous ridge system extending for thousands of kilometers.

- Central rift valley: A valley running along the axis of the ridge.

- Volcanic activity: Frequent underwater volcanic eruptions.

- Hydrothermal vents: Locations where hot, mineral-rich water is released into the ocean.

- Seafloor spreading: The process of new oceanic crust formation.

- Current Activity: Continuous seafloor spreading, frequent minor earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. The rate of spreading varies along the ridge.

Comparison Table of Rift Zones

Below is a table comparing the Atlantic Rift, the East African Rift, and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, highlighting key differences and similarities.

| Rift Zone | Plate Boundary Type | Key Features | Current Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Rift | Divergent (Oceanic) | Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Central Rift Valley, Seafloor Spreading, Hydrothermal Vents | Seafloor spreading at varying rates, minor earthquakes, and volcanic activity. |

| East African Rift | Divergent (Continental) | Rift Valleys, Volcanoes, Faults, Lakes | Ongoing continental rifting, frequent earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. |

| Mid-Atlantic Ridge | Divergent (Oceanic) | Underwater Mountain Range, Central Rift Valley, Volcanic Activity, Hydrothermal Vents, Seafloor Spreading | Continuous seafloor spreading, frequent minor earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. |

Illustrative Examples and Case Studies

This section delves into specific examples and case studies to illustrate the concepts discussed previously. These examples bring the scientific principles to life, showing how the Atlantic Rift is studied and the fascinating environments it creates.

Hydrothermal Vent Site: The Lost City

The Lost City Hydrothermal Field is an extraordinary example of a hydrothermal vent system. Located on the Atlantis Massif in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, it’s a site that challenges many preconceived notions about hydrothermal vents.The Lost City differs significantly from other known vent fields. Instead of being directly associated with volcanic activity, it’s located on a fault scarp, approximately 15 kilometers west of the main spreading axis.

The vents here are formed from the interaction of seawater with mantle rocks, specifically serpentinized peridotite. This process, called serpentinization, produces alkaline fluids that are highly enriched in methane and hydrogen.The unique characteristics of the Lost City include:

- Location: Situated on the Atlantis Massif, west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge spreading center.

- Fluid Composition: The vents emit alkaline fluids, unlike the acidic fluids common in volcanic vent systems. These fluids are rich in methane and hydrogen.

- Vent Structures: The vents build large carbonate structures, some exceeding 60 meters in height. These structures are composed primarily of aragonite and brucite.

- Life Forms: The Lost City supports a unique ecosystem. It’s home to a variety of organisms, including snails, limpets, and specialized microbial communities that thrive on the chemical energy from the vents.

The discovery of the Lost City has provided significant insights into the processes of chemosynthesis, the formation of methane, and the potential for life on other planets. The longevity and stability of the Lost City also suggest that similar systems may exist elsewhere in the universe.

Seafloor Spreading Model

Seafloor spreading is a fundamental process in plate tectonics, driving the movement of continents and creating new oceanic crust. The following step-by-step model demonstrates this process:

1. Magma Upwelling

Beneath the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, mantle rocks experience decompression melting, producing magma. This magma is less dense than the surrounding rock and rises toward the surface.

2. Crust Formation

As the magma reaches the seafloor, it erupts, forming new oceanic crust. This new crust is primarily composed of basalt. The basalt solidifies as it cools in contact with seawater.

3. Ridge Axis

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge acts as the site where new oceanic crust is created. The ridge is characterized by a central rift valley, where the newly formed crust is thinnest and where volcanic activity is most prevalent.

4. Spreading

As new crust forms, it pushes the older crust away from the ridge axis in both directions. This movement is driven by the upwelling magma and the density difference between the hot, newly formed crust and the cooler, older crust.

5. Crustal Cooling and Subsidence

As the oceanic crust moves away from the ridge, it cools and becomes denser. This cooling causes the crust to subside, increasing the water depth.

6. Subduction (eventually)

Over millions of years, the oceanic crust eventually reaches subduction zones, where it is forced beneath a continental plate or another oceanic plate, returning the material to the mantle. This process closes the cycle of plate tecttonics.The rate of seafloor spreading varies across different parts of the Atlantic. The average rate is about 2.5 centimeters per year, which is equivalent to about the growth of a fingernail.

Monitoring Volcanic Activity in the Atlantic Rift

Scientists employ various methods to monitor and study volcanic activity in the Atlantic Rift. This monitoring is crucial for understanding the processes of plate tectonics, assessing potential hazards, and gaining insights into the Earth’s interior.Here are some of the key methods used:

- Seismic Monitoring: Seismometers are deployed on the seafloor and on land to detect and record earthquakes. The frequency, magnitude, and location of earthquakes provide information about the movement of magma and the stresses within the Earth’s crust.

- Hydroacoustic Monitoring: Hydrophones are used to listen for underwater sounds, including those produced by volcanic eruptions. These sounds can travel long distances through the water and provide valuable information about eruptive activity.

- Ocean Bottom Pressure Sensors: These instruments measure changes in water pressure on the seafloor, which can indicate volcanic inflation or deflation, often preceding or accompanying eruptions.

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): AUVs equipped with various sensors are used to map the seafloor, collect water samples, and conduct detailed surveys of volcanic features. These vehicles can access areas that are difficult or impossible for manned submersibles to reach.

- Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs): ROVs are tethered to surface ships and provide real-time video and data from the seafloor. They can be used to observe volcanic eruptions, collect samples, and study hydrothermal vents.

- Water Column Chemistry Analysis: Scientists analyze the chemical composition of the water column to detect changes associated with volcanic activity, such as the release of gases and dissolved minerals.

- Satellite Monitoring: Satellites equipped with various sensors can be used to monitor the sea surface temperature, detect changes in the ocean’s color, and measure the height of the sea surface. These data can provide valuable information about volcanic activity.

By using these diverse methods, scientists have gained a comprehensive understanding of volcanic activity in the Atlantic Rift, allowing for better hazard assessment and improved models of plate tectonic processes.

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, the Atlantic Rift stands as a testament to the powerful forces shaping our world. From the slow, steady separation of tectonic plates to the vibrant ecosystems thriving in the depths, the Atlantic Rift offers a glimpse into the dynamic processes that define our planet. Exploring this underwater realm allows us to appreciate the ongoing evolution of Earth and the interconnectedness of all its systems, inspiring continued research and wonder.

User Queries

How deep is the Atlantic Rift?

The depth of the Atlantic Rift varies, but the Mid-Atlantic Ridge generally lies between 2,000 to 3,000 meters (6,600 to 9,800 feet) below the sea surface. Some areas are shallower, while others are significantly deeper.

How fast does the Atlantic Ocean widen?

The Atlantic Ocean is widening at a rate of about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) per year on average. This rate can vary in different sections of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Are there any hazards associated with the Atlantic Rift?

Yes, the Atlantic Rift has potential hazards, including volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. While most activity occurs underwater, these events can sometimes trigger tsunamis or affect coastal regions.

What kind of resources can be found in the Atlantic Rift?

The Atlantic Rift has potential mineral resources, including polymetallic sulfides, which are rich in metals like copper, zinc, and gold. Hydrothermal vents can also be a source of valuable minerals.

How do scientists study the Atlantic Rift?

Scientists use various methods to study the Atlantic Rift, including remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and deep-sea drilling. They also analyze seismic data and water samples to understand the geological and biological processes at work.