Malaria, a disease that casts a long shadow over Zambia, continues to pose significant public health challenges. But what if we could predict where and when outbreaks will occur, giving us a head start in protecting vulnerable communities? This is where the innovative use of remote sensing satellite data comes into play, offering a powerful tool to understand and anticipate malaria’s movements.

By harnessing the power of satellites like Landsat and Sentinel, we can gather crucial information about environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, and vegetation, which are all key players in the malaria transmission cycle. This data, combined with advanced modeling techniques, allows us to create predictive maps, pinpointing areas at high risk and enabling targeted interventions to save lives.

Introduction

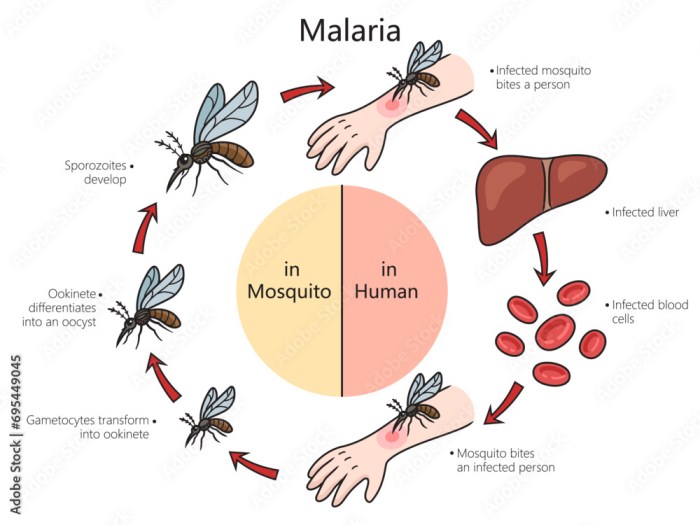

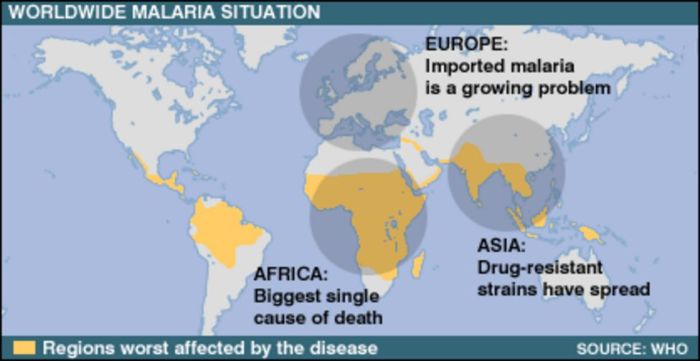

Malaria, a life-threatening disease caused by parasites transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes, poses a significant public health challenge globally, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In Zambia, malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, disproportionately affecting children under five years old and pregnant women. The disease places a considerable burden on the healthcare system, hindering economic development and social well-being.Predicting malaria outbreaks at the sub-district level is crucial for effective disease control and prevention.

This granular level of analysis allows for targeted interventions, resource allocation, and timely responses to emerging threats. By identifying areas at high risk, health officials can implement preventive measures such as insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and prompt diagnosis and treatment, ultimately reducing the incidence and impact of malaria. Remote sensing satellite data offers a powerful tool for achieving this goal.

Malaria’s Impact in Zambia

Malaria’s impact in Zambia is substantial, contributing significantly to the national disease burden. The disease leads to a considerable number of hospitalizations and deaths annually, straining healthcare resources and affecting the productivity of the population. Malaria also has indirect consequences, such as school absenteeism and reduced economic activity.

The Importance of Sub-District Level Prediction

Predicting malaria outbreaks at the sub-district level enables a more focused and effective response. This localized approach allows for the tailoring of interventions to specific areas based on their unique environmental and epidemiological characteristics.

- Targeted Interventions: Interventions like insecticide-treated bed net distribution, indoor residual spraying, and chemoprophylaxis can be directed to the most vulnerable populations and high-risk areas. For example, in a sub-district experiencing a surge in malaria cases, targeted spraying campaigns can be rapidly deployed to reduce mosquito populations and transmission.

- Resource Allocation: Limited resources, including funding, personnel, and supplies, can be efficiently allocated to areas where they are most needed. This ensures that resources are not spread thinly across the entire country but are concentrated where they can have the greatest impact.

- Early Warning Systems: Sub-district level predictions facilitate the development of early warning systems. These systems use predictive models to alert health officials to potential outbreaks, allowing them to prepare for increased patient loads and ensure adequate medical supplies.

- Enhanced Surveillance: Sub-district level predictions can improve disease surveillance efforts. By identifying areas at high risk, health officials can intensify surveillance activities, such as active case detection and mosquito monitoring, to detect outbreaks early and prevent their spread.

Benefits of Using Remote Sensing Satellite Data

Remote sensing satellite data offers several advantages for predicting malaria outbreaks, including providing readily available and cost-effective data on environmental factors that influence malaria transmission. This data can be integrated into predictive models to identify high-risk areas and forecast outbreaks.

- Environmental Factors: Remote sensing can capture data on environmental factors that are closely linked to malaria transmission, such as:

- Vegetation Indices: Measurements like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) can indicate areas of lush vegetation, which can serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes. High NDVI values often correlate with increased mosquito populations and malaria risk.

- Surface Water: Satellite imagery can identify areas of standing water, such as swamps, ponds, and flooded areas, which are prime breeding sites for mosquitoes. Mapping these water bodies helps assess potential mosquito habitats.

- Land Surface Temperature: Temperature data from satellites can reveal thermal patterns, which can influence mosquito development and the malaria parasite’s lifecycle. Warmer temperatures generally accelerate these processes, increasing the risk of transmission.

- Rainfall: Satellite-derived rainfall data helps in understanding the relationship between rainfall patterns and mosquito breeding. Excessive rainfall can lead to flooding and the creation of breeding habitats.

- Cost-Effectiveness and Accessibility: Satellite data is often more cost-effective and readily available than ground-based data collection methods, especially in remote areas. This accessibility allows for more frequent and comprehensive monitoring of environmental conditions.

- Improved Predictive Models: Integrating remote sensing data into predictive models enhances their accuracy and effectiveness. By incorporating environmental factors, these models can better identify areas at risk of outbreaks and predict future trends.

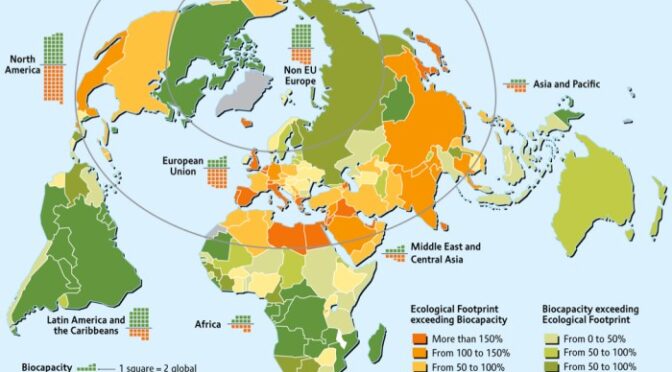

- Scalability: Remote sensing data can be applied across large geographic areas, allowing for national-level malaria monitoring and control programs. This scalability is particularly important in countries like Zambia, where malaria transmission varies significantly across different regions.

Malaria and Zambia

Source: ftcdn.net

Malaria remains a significant public health challenge in Zambia, impacting the nation’s health and socioeconomic development. Understanding the disease’s prevalence, the obstacles to control, and the environmental factors that fuel its transmission is crucial for effective prediction and intervention strategies.

Malaria Prevalence and Mortality Rates in Zambia

Zambia has historically borne a heavy burden of malaria. While progress has been made in recent years, the disease continues to cause considerable morbidity and mortality, especially among children under five years of age.

- Prevalence: Malaria prevalence varies across the country and by season. According to the Zambia Demographic and Health Survey (ZDHS) data, the prevalence among children under five years of age was approximately 15% in 2018, a decrease from 20% in 2014. However, prevalence can be much higher in certain areas and during the rainy season.

- Mortality: Malaria is a leading cause of death in Zambia, particularly for young children. While mortality rates have decreased due to interventions like insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and effective treatment, malaria still accounts for a significant proportion of deaths in the country.

- Data Sources: Information on malaria prevalence and mortality is collected through surveys such as the ZDHS, routine health facility data, and the Zambia National Malaria Elimination Programme (ZNMEP).

Challenges in Controlling Malaria in Zambia

Despite concerted efforts, several challenges impede the effective control of malaria in Zambia. Addressing these obstacles is essential for achieving the goal of malaria elimination.

- Drug Resistance: The emergence and spread of drug-resistant malaria parasites, particularly to artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), pose a serious threat. Regular monitoring of drug efficacy is vital to inform treatment policies.

- Insecticide Resistance: Mosquitoes are developing resistance to the insecticides used in ITNs and indoor residual spraying (IRS). This reduces the effectiveness of these key interventions.

- Access to Healthcare: Difficulties in accessing prompt and effective malaria diagnosis and treatment, especially in remote areas, are a major barrier. This includes challenges related to transportation, infrastructure, and the availability of trained healthcare workers.

- Behavioral Factors: Community knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding malaria prevention and treatment influence the effectiveness of control programs. These include the consistent use of ITNs, seeking prompt medical care when symptoms appear, and understanding the importance of IRS.

- Funding and Resources: Sustained funding and resources are essential for implementing and scaling up malaria control interventions. This includes financial support for program implementation, procurement of commodities (e.g., ITNs, drugs), and training of healthcare workers.

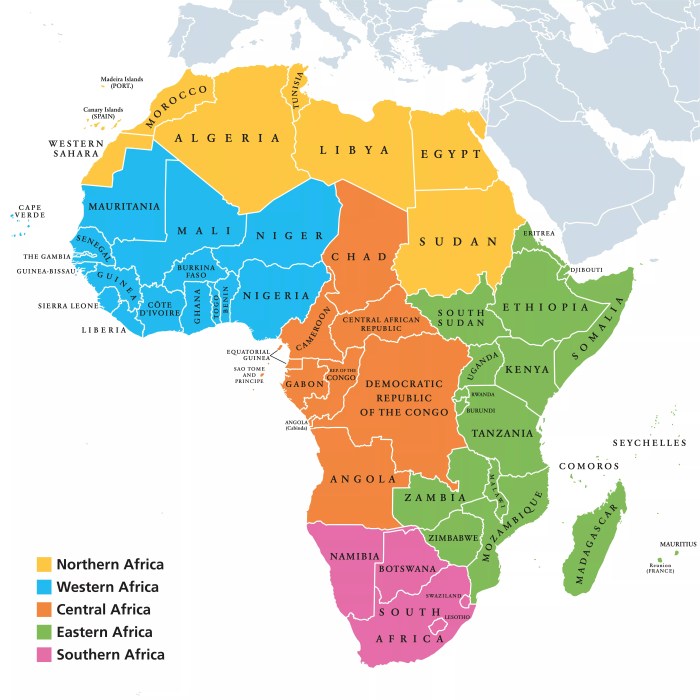

Geographical and Environmental Factors Contributing to Malaria Transmission in Zambia

The geographical and environmental characteristics of Zambia create favorable conditions for malaria transmission. Understanding these factors is crucial for predicting outbreaks and targeting interventions effectively.

- Climate: Zambia experiences a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. The rainy season, typically from November to April, provides ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes, leading to increased malaria transmission.

- Altitude: Malaria transmission is generally higher in low-lying areas. The Zambezi and Luangwa Valleys, for instance, are known to have high malaria prevalence due to their lower altitudes and warmer temperatures.

- Water Bodies: Standing water bodies, such as swamps, rivers, and man-made reservoirs, provide breeding sites for mosquitoes. The presence of these water sources is a key factor in malaria transmission. For example, the Kafue Flats, a large wetland area, is associated with high malaria prevalence due to its extensive water coverage.

- Vegetation: Dense vegetation can provide shade and shelter for mosquitoes, increasing their survival rates. Areas with lush vegetation often have higher malaria transmission rates.

- Deforestation and Land Use Changes: Changes in land use, such as deforestation and agricultural practices, can alter mosquito breeding habitats and affect malaria transmission patterns.

- Population Density: Areas with higher population densities may experience increased malaria transmission due to higher human-mosquito contact.

Remote Sensing Data for Malaria Prediction

Source: co.uk

Remote sensing data plays a crucial role in predicting malaria outbreaks. By analyzing data collected from satellites, we can gain valuable insights into environmental factors that influence mosquito breeding and malaria transmission. This information is critical for proactive public health interventions, helping to prevent and control the spread of the disease.

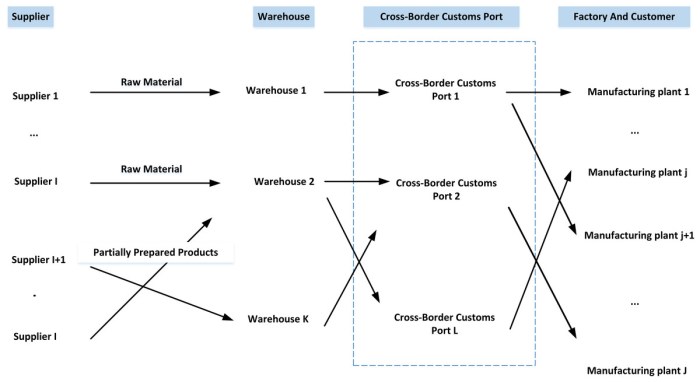

Data Sources

Various types of remote sensing data are suitable for malaria prediction, each providing unique information about the environment. These data sources offer different spatial and temporal resolutions, which are essential considerations when analyzing data at the sub-district level.

- Vegetation Indices: Vegetation indices, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), are derived from satellite data and provide information on vegetation health and density. These indices are crucial because they can indicate areas with stagnant water and lush vegetation, which are ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

- Land Surface Temperature (LST): LST data helps to monitor temperature variations across the landscape. Mosquito activity and malaria transmission are highly sensitive to temperature. Warmer temperatures can accelerate the mosquito life cycle and increase the rate of parasite development within the mosquito.

- Precipitation Data: Rainfall patterns are a significant factor in malaria transmission. Remote sensing data can provide information on rainfall amounts and distribution. This data is critical because heavy rainfall can create breeding sites, while drought can concentrate mosquito populations in available water sources.

- Surface Water Extent: Mapping surface water is vital for identifying potential mosquito breeding habitats. Remote sensing data can detect and monitor standing water bodies like ponds, swamps, and flooded areas. This data helps pinpoint locations at high risk of malaria transmission.

Several satellite missions provide the necessary data for malaria prediction. The choice of mission depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, including spatial and temporal resolution needs. For sub-district level analysis, high spatial resolution data is often preferred to accurately map environmental features.

- Landsat: The Landsat program provides a long-term record of Earth’s land surface, offering valuable data for malaria prediction.

- Data Products: Landsat satellites provide data on vegetation indices (NDVI), land surface temperature (LST), and land cover.

- Spatial Resolution: Landsat data typically has a spatial resolution of 30 meters, meaning each pixel represents an area of 30 meters by 30 meters on the ground. This resolution is suitable for sub-district level analysis.

- Temporal Resolution: Landsat satellites have a temporal resolution of approximately 16 days, meaning they revisit the same location every 16 days.

- Sentinel: The European Space Agency’s Sentinel missions provide free and open data with high spatial and temporal resolutions.

- Data Products: Sentinel-2 offers high-resolution multispectral imagery suitable for calculating vegetation indices, while Sentinel-3 provides data on sea and land surface temperature.

- Spatial Resolution: Sentinel-2 data has a spatial resolution of 10-60 meters, depending on the spectral band.

- Temporal Resolution: Sentinel-2 has a revisit time of 5 days, and Sentinel-3 has a revisit time of 1-2 days. This improved temporal resolution allows for more frequent monitoring of environmental changes.

- MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer): MODIS instruments, aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites, provide data with a broad spatial coverage and moderate resolution.

- Data Products: MODIS data includes vegetation indices (NDVI), land surface temperature (LST), and precipitation estimates.

- Spatial Resolution: MODIS data typically has a spatial resolution ranging from 250 meters to 1 kilometer.

- Temporal Resolution: MODIS has a daily temporal resolution, allowing for frequent monitoring of environmental conditions.

The spatial and temporal resolutions of these data sources have significant implications for sub-district level analysis. High spatial resolution data, like that from Landsat and Sentinel-2, allows for detailed mapping of environmental features, enabling accurate identification of mosquito breeding sites within a sub-district. A high temporal resolution, such as that provided by MODIS and Sentinel, allows for frequent monitoring of environmental changes, which is crucial for tracking the dynamic relationship between environmental factors and malaria transmission.

For example, imagine a scenario where a sub-district in Zambia experiences heavy rainfall. Using high-resolution satellite data, such as Sentinel-2, public health officials can quickly identify areas of standing water that may serve as mosquito breeding sites. Simultaneously, by monitoring land surface temperature data from MODIS, they can assess the impact of temperature on mosquito development. This combined information allows for a targeted response, such as distributing insecticide-treated nets or spraying larvicides in the most vulnerable areas, improving the efficiency of malaria control efforts.

Environmental Variables and Malaria: The Correlation

Understanding how environmental factors contribute to malaria transmission is crucial for effective prediction and control. These factors influence the life cycle of both thePlasmodium* parasite and the Anopheles mosquito, the vector responsible for malaria transmission. By analyzing environmental data, we can identify areas at higher risk and implement targeted interventions.

Influence of Temperature, Rainfall, and Vegetation on Malaria Transmission

Several environmental variables play a significant role in malaria transmission. These variables affect different stages of the parasite’s and mosquito’s life cycles, influencing the rate of transmission.Temperature is a key factor influencing the mosquito’s development and the parasite’s maturation within the mosquito. Higher temperatures generally accelerate these processes. The speed at which the parasite develops inside the mosquito, a process called the extrinsic incubation period, is directly affected by temperature.Rainfall creates breeding sites for mosquitoes, such as stagnant water bodies.

The availability of these sites is directly linked to mosquito population size. Heavy rainfall can also wash away mosquito larvae, while moderate rainfall maintains optimal breeding conditions.Vegetation, measured using vegetation indices, provides shelter and food sources for mosquitoes. Dense vegetation cover can increase the mosquito population and consequently increase malaria transmission. Vegetation also influences the local microclimate, affecting temperature and humidity.

Relationship Between Environmental Variables and Life Cycle

The relationship between environmental variables and the life cycle of the malaria parasite and its mosquito vector is complex. It involves several interactions.The mosquito vector’s life cycle, from egg to adult, is highly dependent on temperature and rainfall. Warmer temperatures speed up larval development, while rainfall creates the necessary aquatic habitats. Mosquito survival rates are also affected by these factors; for example, high temperatures and humidity can increase mosquito lifespan, thus increasing the chance of parasite transmission.The parasite’s life cycle within the mosquito, from ingestion during a blood meal to the infectious stage, is also temperature-dependent.

The parasite requires a certain temperature range to complete its development, with higher temperatures shortening the incubation period.

Environmental Variables, Remote Sensing Data, and Malaria Transmission

Remote sensing data provides valuable information on environmental variables relevant to malaria transmission. The following table summarizes these variables, data sources, and their link to malaria transmission.

| Environmental Variable | Remote Sensing Data Source | Link to Malaria Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Land Surface Temperature (LST) from MODIS, Sentinel-3 | Affects mosquito development and parasite incubation period. Higher temperatures accelerate both. |

| Rainfall | TRMM, GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) | Creates breeding sites for mosquitoes. Heavy rainfall can wash away larvae, while moderate rainfall maintains breeding grounds. |

| Vegetation Indices (NDVI, EVI) | MODIS, Landsat | Provides habitat and food for mosquitoes. Higher vegetation cover often correlates with increased mosquito populations. |

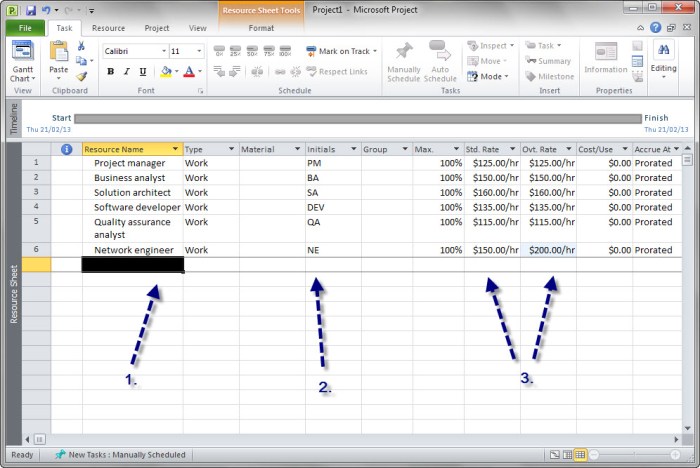

Data Preprocessing and Preparation

Preparing the data is a crucial step in predicting malaria outbreaks. This involves cleaning, correcting, and integrating various datasets to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the prediction models. The following sections detail the essential steps in this process.

Preprocessing Remote Sensing Data

Before using satellite data, it needs careful preprocessing to correct for errors and artifacts introduced during data acquisition and transmission. These corrections are essential to ensure the data accurately reflects the environmental conditions on the ground.

- Atmospheric Correction: This removes the effects of the atmosphere (e.g., scattering and absorption of sunlight by aerosols and gases) on the satellite-measured reflectance. Atmospheric correction is vital because the atmosphere can significantly alter the signal received by the satellite, leading to inaccurate estimations of surface properties. Several methods are available, including:

- Radiative Transfer Models: These models simulate the interaction of radiation with the atmosphere, allowing for the correction of atmospheric effects.

Examples include the Second Simulation of the Satellite Signal in the Solar Spectrum (6S) model and the Atmospheric Correction for Flat Terrain (FLAASH) model.

- Empirical Methods: These methods use ground measurements and satellite data to empirically derive atmospheric correction parameters.

- Radiative Transfer Models: These models simulate the interaction of radiation with the atmosphere, allowing for the correction of atmospheric effects.

- Geometric Correction: This corrects for geometric distortions in the satellite imagery caused by factors like the Earth’s curvature, satellite viewing angle, and sensor characteristics. Geometric correction ensures that the pixels in the image are accurately located geographically. Common methods include:

- Orthorectification: This process removes geometric distortions using a digital elevation model (DEM) and satellite sensor information to create a geometrically accurate image.

- Image-to-Image Registration: This aligns the satellite imagery to a reference image with known geometric accuracy.

- Radiometric Correction: This corrects for variations in the satellite sensor’s response and converts the raw digital numbers (DNs) into physically meaningful units, such as reflectance or radiance. This is crucial for comparing data from different dates or sensors. Methods include:

- Calibration: This uses pre-launch or on-board calibration data to convert DNs to radiance.

- Dark Object Subtraction: This method estimates and subtracts the atmospheric path radiance from the image.

Extracting Environmental Variables from Satellite Data

After preprocessing, the next step involves extracting relevant environmental variables from the satellite data. These variables are then used as predictors in the malaria outbreak prediction models.

- Vegetation Indices: These indices, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), provide information on vegetation health and density. Higher NDVI values often indicate more vigorous vegetation growth, which can correlate with mosquito breeding habitats.

NDVI = (NIR – Red) / (NIR + Red)

Where NIR is the near-infrared band, and Red is the red band.

- Land Surface Temperature (LST): LST is the temperature of the Earth’s surface, which can influence mosquito development rates and malaria transmission. LST can be derived from thermal infrared bands on satellites like Landsat and MODIS.

- Water Body Detection: Identifying and mapping water bodies is crucial, as they serve as breeding sites for mosquitoes. This can be done using the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) or by analyzing the spectral characteristics of water in satellite imagery.

NDWI = (Green – NIR) / (Green + NIR)

Where Green is the green band, and NIR is the near-infrared band.

- Rainfall Estimation: Although satellite rainfall products are not direct measurements, they can provide estimates of rainfall patterns. Data from satellites like the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) and the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) can be used.

Integrating Remote Sensing Data with Other Datasets

Integrating remote sensing data with other datasets is essential for a comprehensive understanding of malaria outbreaks. This involves combining environmental data with climate and epidemiological data.

- Climate Data: Climate data, such as rainfall, temperature, and humidity, are crucial for understanding the environmental factors that influence malaria transmission. These data can be obtained from ground-based weather stations or from climate models.

- Rainfall: Rainfall data from ground stations can be combined with satellite rainfall estimates to create a more accurate rainfall dataset.

- Temperature and Humidity: These data can be obtained from weather stations and used to correlate with mosquito development and malaria transmission rates.

- Epidemiological Data: This includes data on malaria cases, incidence rates, and prevalence. This data is essential for training and validating the prediction models.

- Malaria Case Data: Data on the number of malaria cases reported at the sub-district level.

- Malaria Incidence Rates: Calculating the number of new malaria cases per unit of population over a specific period.

- Malaria Prevalence: The proportion of a population infected with malaria at a given time.

- Geographic Information System (GIS) Integration: All datasets are integrated within a GIS environment. This allows for spatial analysis and the creation of predictive models.

- Spatial Alignment: Ensuring all datasets are spatially aligned using common coordinate systems.

- Data Fusion: Combining data from multiple sources to create new variables or improve existing ones.

Predictive Modeling Techniques

Source: nyt.com

Predicting malaria outbreaks accurately is crucial for effective public health interventions. Several modeling techniques can be employed to leverage remote sensing data and environmental variables for this purpose. The choice of the most appropriate technique depends on factors like data availability, complexity of the relationships between variables, and desired level of accuracy. This section explores various modeling approaches, their pros and cons, and the steps involved in developing a predictive model.

Statistical Models

Statistical models offer a well-established framework for understanding relationships between variables and predicting outcomes. These models are often easier to interpret than more complex machine learning approaches. They provide insights into the statistical significance of various factors contributing to malaria outbreaks.Statistical models suitable for malaria prediction include:

- Regression Models: These models establish a relationship between a dependent variable (malaria incidence) and one or more independent variables (environmental factors and remote sensing data).

- Linear Regression: This is a basic model assuming a linear relationship. While simple, it might not capture the complex, non-linear relationships often seen in ecological systems.

- Poisson Regression: This is used when the dependent variable is count data, such as the number of malaria cases. It accounts for the non-negative and discrete nature of the data.

- Negative Binomial Regression: This model is used when the malaria case data exhibits overdispersion (variance greater than the mean), which is common in real-world scenarios.

- Logistic Regression: Suitable when the outcome is binary (e.g., presence or absence of an outbreak).

- Time Series Analysis: This analyzes data collected over time to identify trends, seasonality, and patterns. It can be used to predict future malaria incidence based on past data.

- Generalized Additive Models (GAMs): GAMs are an extension of regression models, allowing for non-linear relationships between variables. They can model complex environmental influences on malaria incidence more effectively than linear models.

The primary advantage of statistical models is their interpretability; the coefficients of the model can be directly interpreted to understand the impact of each variable. However, these models may struggle with complex, non-linear relationships. Furthermore, they often require assumptions about the data distribution that might not always hold true. For instance, the use of a linear model might not be appropriate if the relationship between rainfall and malaria incidence is non-linear.

Machine Learning Models

Machine learning models are powerful tools for pattern recognition and prediction, especially in complex systems. They can handle large datasets and capture intricate relationships that might be missed by simpler statistical models.Machine learning models for malaria prediction include:

- Decision Trees: These models create a tree-like structure of decisions to classify or predict outcomes. They are easy to visualize and understand.

- Random Forests: An ensemble method that combines multiple decision trees, improving predictive accuracy and robustness. Random forests are less prone to overfitting than individual decision trees.

- Support Vector Machines (SVMs): SVMs are effective in classifying data by finding the optimal hyperplane that separates different classes. They are well-suited for high-dimensional data.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): ANNs, particularly deep learning models, can learn complex patterns from data. They are capable of handling non-linear relationships but require large datasets and significant computational resources.

- Gradient Boosting Machines: These are ensemble methods that sequentially build decision trees, with each tree correcting the errors of the previous ones. Examples include XGBoost and LightGBM.

Machine learning models often provide higher predictive accuracy compared to statistical models, particularly when dealing with complex datasets. They are able to identify subtle patterns that humans might miss. However, they can be “black boxes,” making it difficult to understand the exact influence of each variable. They also require careful tuning and validation to avoid overfitting. For example, a neural network with too many layers might fit the training data perfectly but perform poorly on new data.

Hybrid Models

Hybrid models combine elements of both statistical and machine learning approaches. They aim to leverage the strengths of each method. For instance, one could use a statistical model to pre-process data or incorporate domain expertise, and then use machine learning to build the final predictive model.

Steps in Developing a Predictive Model (Example: Random Forest)

The following steps Artikel the process of building a predictive model using Random Forest, a popular machine learning technique.

- Data Preparation: This includes cleaning the data, handling missing values, and transforming variables. The data is often split into training and testing sets.

- Feature Selection: Identify the relevant environmental variables and remote sensing data to include in the model. This can be done using domain knowledge or feature importance scores from other models.

- Model Training: Train the Random Forest model using the training data. This involves specifying the number of trees, the maximum depth of the trees, and other parameters.

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model’s performance on the testing data. Metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score are used to assess the model’s predictive ability. Cross-validation techniques can be employed for a more robust evaluation.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize the model’s parameters (hyperparameters) to improve its performance. This can be done using techniques like grid search or random search.

- Model Deployment: Deploy the model to predict malaria outbreaks. This might involve integrating the model into a software system or generating regular reports.

- Model Monitoring and Evaluation: Continuously monitor the model’s performance and update it as needed. This ensures the model remains accurate over time, especially as environmental conditions and malaria transmission dynamics change.

The choice of modeling technique and the specific steps involved will depend on the characteristics of the data, the goals of the prediction, and the resources available. For example, if the goal is to create an easily understandable model for policymakers, a simpler statistical model might be preferred. If the goal is to achieve the highest possible accuracy, a more complex machine learning model may be necessary.

Model Development and Training

Now, let’s dive into the core of our malaria outbreak prediction project: building and training the predictive models. This section will detail the crucial steps involved in transforming our prepared data into a functional prediction tool, including dataset preparation, model construction, and performance evaluation.

Selecting and Preparing Training and Testing Datasets

The success of any predictive model hinges on the quality and representativeness of the data it’s trained on. We meticulously prepare our data for model training and evaluation by splitting it into two key sets: training and testing.First, we need to decide on the proportion of data for training and testing. A common split is 70/30 or 80/20, where the larger portion is used for training the model and the smaller portion for evaluating its performance.

In our case, let’s assume we’ve chosen an 80/20 split.

- Training Dataset: This dataset, representing 80% of our data, is used to teach the model the patterns and relationships between environmental variables and malaria incidence. The model learns from this data, adjusting its internal parameters to minimize prediction errors.

- Testing Dataset: The remaining 20% of the data constitutes the testing dataset. This dataset is kept separate from the training data and is used to evaluate the model’s performance on unseen data. This provides an unbiased assessment of how well the model generalizes to new situations.

We also need to ensure our data is properly formatted and scaled before training. This may involve:

- Data Cleaning: Handling missing values and outliers in our data. Missing values can be imputed using various techniques (mean, median, or more sophisticated methods), while outliers can be addressed through winsorizing or other robust statistical methods.

- Feature Scaling: Scaling numerical features to a similar range (e.g., using standardization or min-max scaling). This prevents features with larger values from dominating the model and improves training efficiency.

For example, imagine we have temperature data ranging from 15°C to 35°C, while rainfall data ranges from 0mm to 200mm. Without scaling, the rainfall data might disproportionately influence the model. Scaling brings these features to a comparable scale.

Building and Training a Predictive Model

With our datasets prepared, we can now build and train our predictive model. The choice of model depends on various factors, including the nature of the data, the desired accuracy, and the computational resources available. In this context, let’s consider the use of a Random Forest model, a popular choice for classification tasks like predicting malaria outbreaks.The Random Forest model is an ensemble learning method that builds multiple decision trees and combines their predictions.

This approach helps to reduce overfitting and improve predictive accuracy.Here are the key steps involved in building and training the Random Forest model:

- Model Selection: We select the Random Forest algorithm from a suitable machine learning library, such as scikit-learn in Python.

- Model Initialization: We initialize the Random Forest model with specific parameters. These parameters control aspects of the model, such as the number of trees in the forest (e.g., 100 or 200 trees), the maximum depth of the trees, and the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node.

- Model Training: We train the model using the training dataset. The model learns the relationships between the environmental variables and malaria incidence by building multiple decision trees.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: We might tune the model’s hyperparameters using techniques like cross-validation to optimize its performance. This involves testing different combinations of parameter values and selecting the combination that yields the best results on a validation set.

After training, the model is ready to make predictions. When provided with a new set of environmental data (e.g., temperature, rainfall, and vegetation indices for a specific sub-district), the model will predict the probability of a malaria outbreak.

Evaluating Model Performance

Once the model is trained, we must evaluate its performance to determine how well it predicts malaria outbreaks. We use various metrics to assess the model’s accuracy, precision, recall, and overall effectiveness.Here are some key evaluation metrics:

- Accuracy: The overall proportion of correctly predicted instances. It’s calculated as:

Accuracy = (Number of Correct Predictions) / (Total Number of Predictions)

While useful, accuracy can be misleading if the dataset has an imbalanced class distribution (e.g., significantly more non-outbreak cases than outbreak cases).

- Precision: The proportion of correctly predicted outbreak cases out of all instances predicted as outbreaks. It’s calculated as:

Precision = (True Positives) / (True Positives + False Positives)

High precision indicates that when the model predicts an outbreak, it’s usually correct.

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of correctly predicted outbreak cases out of all actual outbreak cases. It’s calculated as:

Recall = (True Positives) / (True Positives + False Negatives)

High recall indicates that the model is good at identifying all actual outbreak cases.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall. It provides a balanced measure of the model’s performance, considering both precision and recall. It’s calculated as:

F1-Score = 2

– (Precision

– Recall) / (Precision + Recall)A higher F1-score indicates a better balance between precision and recall.

For instance, consider a scenario where the model predicts 100 potential outbreak cases. Out of these, 80 are actual outbreaks (True Positives), and 20 are not (False Positives). Additionally, there are 20 actual outbreaks that the model missed (False Negatives).

- Accuracy: (80 + Correctly Predicted Non-Outbreak) / (Total Number of Predictions) (This depends on how many non-outbreaks were correctly predicted).

- Precision: 80 / (80 + 20) = 0.80 (80% of the predicted outbreaks are correct).

- Recall: 80 / (80 + 20) = 0.80 (The model identifies 80% of the actual outbreaks).

- F1-Score: 2

– (0.80

– 0.80) / (0.80 + 0.80) = 0.80 (A balanced measure of precision and recall).

These metrics provide a comprehensive view of the model’s performance, allowing us to assess its strengths and weaknesses and refine the model further if necessary. This evaluation process is crucial for ensuring the reliability and usefulness of the malaria outbreak prediction model.

Model Validation and Evaluation

After building a predictive model, it’s crucial to assess how well it performs. This involves validating the model’s predictions and evaluating its performance on data the model hasn’t seen before. The goal is to ensure the model generalizes well to new situations and provides reliable predictions of malaria outbreaks.

Validation Methods

Several methods are used to validate the model’s predictions. These methods help confirm the model’s accuracy and robustness.

- Hold-out Validation: The dataset is split into training and testing sets. The model is trained on the training data and evaluated on the testing data. This provides a straightforward measure of the model’s performance on unseen data.

- K-fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is divided into

-k* folds. The model is trained on

-k-1* folds and validated on the remaining fold. This process is repeated

-k* times, with each fold used as the validation set once. The results are then averaged to provide a more robust estimate of the model’s performance. - Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV): Each data point is used as a validation set, and the model is trained on the remaining data points. This is a computationally intensive method, but it can provide a good estimate of the model’s performance, especially for small datasets.

Performance Assessment Techniques

Several techniques are used to assess the model’s performance on unseen data. These metrics quantify the accuracy and reliability of the model’s predictions.

- Accuracy: The proportion of correctly predicted malaria outbreak occurrences. It is calculated as (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total number of observations.

- Precision: The proportion of predicted positive cases that are actually positive. It is calculated as True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives). High precision indicates fewer false positives.

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positive cases that are correctly identified. It is calculated as True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives). High recall indicates fewer false negatives.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall. It provides a balanced measure of the model’s performance, especially when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

- Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC): A measure of the model’s ability to discriminate between positive and negative cases. AUC ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher value indicating better performance.

- Confusion Matrix: A table that summarizes the performance of a classification model by showing the counts of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives.

Model Output and Interpretation

Here’s a hypothetical example of the model’s output and its interpretation. This illustrates how the model’s predictions would be used in a real-world scenario.

Scenario: The model predicts a high risk of a malaria outbreak in a specific sub-district of Zambia for the upcoming month. The model outputs a probability of 0.85 (85% likelihood) of an outbreak occurring.

Interpretation: Health officials would interpret this as a high-alert situation. This prompts the rapid deployment of resources, such as insecticide-treated bed nets, antimalarial drugs, and vector control measures, to the affected sub-district.The high probability suggests that preventative actions are urgently needed to mitigate a potential malaria outbreak and protect the community’s health. Simultaneously, public health officials would review the environmental variables contributing to this high-risk prediction (e.g., increased rainfall, high temperatures, presence of mosquito breeding sites identified by remote sensing) to better understand the driving factors behind the risk and refine future interventions.

Integration with Public Health Systems

Integrating the malaria prediction model into Zambia’s public health systems is crucial for translating scientific advancements into tangible public health benefits. This integration allows for proactive responses, efficient resource allocation, and ultimately, a reduction in malaria cases and related mortality. The model’s outputs need to be seamlessly incorporated into existing surveillance and intervention strategies.

Incorporating Prediction Outputs into Surveillance Systems

The model’s predictions, which pinpoint areas at high risk of malaria outbreaks, can be directly integrated into Zambia’s existing malaria surveillance system. This system typically involves data collection from health facilities, community health workers, and national malaria control programs.

- Early Warning System Integration: The predictions can function as an early warning system. By providing information on potential outbreaks weeks or months in advance, health officials can proactively prepare for surges in cases. This includes:

- Increased diagnostic testing in high-risk areas.

- Stockpiling antimalarial drugs and supplies.

- Mobilizing health workers for rapid response.

- Geographic Information System (GIS) Integration: The model’s outputs, often in the form of risk maps, can be integrated into a GIS platform used by the Ministry of Health. This allows for spatial analysis, visualization of risk areas, and overlaying of other relevant data, such as:

- Population density.

- Health facility locations.

- Insecticide-treated net distribution.

- Real-time Data Feed: The model can be designed to provide a real-time data feed to the surveillance system. This allows for continuous monitoring of malaria risk and rapid adaptation to changing environmental conditions and malaria prevalence.

Targeted Interventions and Resource Allocation

The prediction model’s outputs are invaluable for informing targeted interventions and optimizing resource allocation. This strategic approach ensures that resources are deployed where they are most needed, maximizing their impact.

- Targeted Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS): IRS, a key malaria control strategy, can be focused on areas identified as high-risk by the model. This prevents spraying in areas where it is unnecessary, optimizing the use of limited resources.

- Distribution of Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs): ITN distribution can be prioritized in predicted high-risk areas. This ensures that the most vulnerable populations receive the protection they need. The model helps to identify areas where ITN coverage may be insufficient.

- Mass Drug Administration (MDA): In specific circumstances, such as during outbreaks or in areas with high transmission, MDA can be implemented. The model helps to identify the populations most at risk and where MDA would be most effective.

- Health Education and Community Mobilization: Targeted health education campaigns can be launched in predicted high-risk areas to raise awareness about malaria prevention and treatment. Community mobilization efforts can be focused on these areas to encourage the adoption of preventative behaviors.

- Resource Allocation Optimization: The model’s predictions can guide the allocation of resources, including:

- Staffing levels at health facilities.

- Procurement of diagnostic tests and drugs.

- Funding for malaria control programs.

Examples of Predictive Models in Guiding Malaria Control Efforts

Predictive models have been successfully employed to guide malaria control efforts in various regions, demonstrating their effectiveness in different contexts. These examples offer valuable insights into how predictive models can be used to improve malaria control.

- Kenya: The Malaria Early Warning System (MEWS) in Kenya utilizes a combination of climate data, entomological data, and historical malaria incidence to predict malaria outbreaks. This system has been used to guide targeted interventions, such as ITN distribution and IRS campaigns. The MEWS has helped to reduce the burden of malaria in several regions of Kenya.

- Tanzania: Researchers developed a predictive model using satellite imagery and environmental data to forecast malaria incidence in Tanzania. The model’s outputs were used to inform resource allocation and targeted interventions, contributing to a decrease in malaria cases.

- Namibia: A study in Namibia used remote sensing data and machine learning to predict malaria risk. The model identified areas with high malaria transmission and helped to prioritize interventions such as IRS and ITN distribution, resulting in more efficient use of resources.

- Southeast Asia: Predictive models are used to identify areas at risk of malaria outbreaks, enabling the implementation of timely interventions. The models incorporate factors such as climate data, vector distribution, and human movement patterns. This information is used to improve the effectiveness of malaria control strategies.

Challenges and Limitations

Predicting malaria outbreaks using remote sensing data, while promising, faces several significant challenges and limitations. These issues can impact the accuracy, reliability, and practical application of the predictive models. It’s crucial to acknowledge these hurdles to refine the methodology and interpret the results cautiously.

Data Availability and Quality

The success of remote sensing-based malaria prediction heavily relies on the availability, quality, and consistency of the data. Several factors can impede this:

- Cloud Cover: Satellite imagery is often obstructed by cloud cover, particularly during the rainy season when malaria transmission is highest. This can lead to gaps in data and reduced temporal resolution, hindering the ability to monitor environmental variables continuously.

- Sensor Calibration and Accuracy: Variations in sensor calibration and accuracy can introduce errors. For instance, differences between satellite sensors (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) can affect the comparability of data over time and across different regions. This necessitates rigorous pre-processing and calibration.

- Spatial Resolution: The spatial resolution of satellite imagery might not always be fine enough to capture localized variations in environmental conditions at the sub-district level. Higher resolution imagery (e.g., from drones or very-high-resolution satellites) can be more expensive and may not be consistently available.

- Data Acquisition Costs: While some satellite data is freely available (e.g., Sentinel), other sources require significant financial investment, potentially limiting access for resource-constrained regions.

- Data Format and Compatibility: Dealing with different data formats and ensuring compatibility across various remote sensing datasets (e.g., different bands, spectral indices) and other data sources (e.g., epidemiological data) can be complex and time-consuming.

Environmental Variable Limitations

While remote sensing can provide valuable information about environmental factors, it’s not without its limitations.

- Indirect Measurements: Remote sensing data provides indirect measurements of environmental variables relevant to malaria. For example, satellite-derived vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) are used as proxies for mosquito breeding sites, but they do not directly measure the presence of water bodies or the abundance of mosquitoes.

- Complex Interactions: Malaria transmission is influenced by complex interactions between environmental, social, and economic factors. Remote sensing can capture environmental variables, but it may not adequately account for the influence of human behavior, access to healthcare, or socioeconomic conditions.

- Lag Times: There is often a time lag between changes in environmental conditions and their impact on malaria transmission. Predictive models need to account for these lag times to provide timely and accurate predictions.

- Variable Specificity: Some crucial environmental factors, such as specific mosquito breeding sites or the presence of insecticide resistance, are difficult or impossible to detect using remote sensing.

Epidemiological Data Challenges

Integrating epidemiological data with remote sensing data presents its own set of challenges.

- Data Accuracy and Completeness: The accuracy and completeness of malaria incidence data at the sub-district level are crucial for training and validating the predictive models. However, data quality can vary due to underreporting, misdiagnosis, and inconsistencies in data collection methods.

- Spatial Mismatch: There might be a mismatch between the spatial resolution of remote sensing data and the spatial units used for reporting malaria incidence (e.g., health facility catchment areas). This can lead to challenges in aligning the data and performing spatial analysis.

- Time Delays in Data Reporting: There can be delays in the reporting of malaria incidence data, which can hinder the real-time application of predictive models for early warning and response.

- Limited Availability of Historical Data: The availability of long-term historical epidemiological data is essential for developing and validating predictive models. However, such data may be limited or unavailable in certain regions, particularly in the case of recent malaria outbreaks.

Model Complexity and Validation

Developing and validating predictive models involves its own set of complexities.

- Model Selection and Parameter Tuning: Choosing the appropriate predictive modeling technique and optimizing model parameters require careful consideration and expertise. Different models (e.g., machine learning algorithms) may have varying performance depending on the data and the specific context.

- Overfitting: Overfitting can occur if the model is too complex and fits the training data too closely, leading to poor performance on unseen data. Regularization techniques and cross-validation are important to mitigate this risk.

- Model Validation: Validating the model using independent datasets is essential to assess its performance and reliability. However, obtaining independent validation datasets can be challenging, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

- Transferability: Models trained in one region may not necessarily be transferable to other regions due to differences in environmental conditions, mosquito species, and other factors. Model adaptation and recalibration may be necessary.

Uncertainty and Error Sources

Several sources of uncertainty and error can affect the accuracy of malaria outbreak predictions.

- Measurement Errors: Errors in the measurement of environmental variables and epidemiological data can propagate through the model, leading to inaccurate predictions.

- Model Assumptions: Predictive models often rely on certain assumptions, such as the linearity of relationships between variables. Violations of these assumptions can lead to errors.

- Data Limitations: As mentioned earlier, data limitations (e.g., cloud cover, incomplete data) can introduce uncertainty and affect model performance.

- Stochasticity: Malaria transmission is a complex process influenced by stochastic (random) factors, such as weather variability and human behavior. It is difficult to fully account for these factors in predictive models.

- Threshold Effects: Predicting outbreaks often involves identifying thresholds for environmental variables or incidence rates. The choice of these thresholds can affect the accuracy of the predictions.

Future Directions and Research

This research area offers significant opportunities for further exploration and refinement. Advancements in technology and modeling techniques hold the potential to dramatically improve the accuracy and impact of malaria outbreak predictions. Continued investigation is crucial to address existing limitations and enhance the usability of these models for public health interventions.

Advancements in Remote Sensing Technology

The evolution of remote sensing offers several avenues for improving malaria prediction. These advancements can provide more detailed and timely information.

- High-Resolution Imagery: The use of higher-resolution satellite imagery, such as that provided by commercial satellites like WorldView or Pleiades, allows for more precise identification of environmental features that influence mosquito breeding sites. This could include the detection of small water bodies, vegetation types, and land cover changes with greater accuracy. This would improve the ability to map mosquito habitats and understand their distribution.

- Hyperspectral Data: Hyperspectral sensors, which capture data in hundreds of narrow spectral bands, can provide detailed information about vegetation health, soil composition, and water quality. This data can be used to identify subtle environmental variations that are correlated with malaria transmission, potentially leading to more accurate predictions. For example, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) can be derived from multispectral data to assess vegetation greenness, and hyperspectral data can provide a more nuanced understanding of vegetation types and conditions.

- Improved Sensor Capabilities: Developing and utilizing sensors capable of detecting specific chemical signatures related to mosquito breeding sites or larval stages could significantly enhance predictive capabilities. These sensors could be deployed on satellites, drones, or even ground-based stations. This is a very active area of research.

- Integration of Novel Data Sources: Integrating data from emerging remote sensing platforms, such as small satellites (CubeSats) and drone-based systems, could provide more frequent and flexible data acquisition. CubeSats, in particular, offer the potential for rapid revisit times, allowing for near real-time monitoring of environmental changes. Drone-based systems can be deployed for targeted data collection in areas with high malaria risk, offering high-resolution data at a lower cost than traditional satellite imagery.

Enhanced Modeling Techniques

Refining the modeling techniques used for malaria prediction is essential. This can lead to increased accuracy and the ability to incorporate more complex factors.

- Advanced Machine Learning Algorithms: Exploring and implementing more sophisticated machine learning algorithms, such as deep learning models (e.g., convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks), could improve prediction accuracy. These models can handle complex, non-linear relationships between environmental variables and malaria incidence. For instance, deep learning models can automatically learn relevant features from satellite imagery, reducing the need for manual feature extraction.

- Ensemble Modeling: Developing ensemble models that combine the predictions of multiple individual models can improve the overall predictive performance. This approach can reduce the impact of individual model biases and provide more robust predictions. Ensemble methods such as Random Forests, Gradient Boosting Machines, and stacking can be employed.

- Incorporating Climate Change Scenarios: Integrating climate change projections into the models is crucial for understanding the future impact of malaria. Climate models can provide projections of temperature, rainfall, and humidity, which can then be used to simulate how malaria transmission patterns might change. This could involve using data from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) to drive the models.

- Developing Spatio-Temporal Models: Employing spatio-temporal modeling techniques can capture the complex relationships between malaria incidence and environmental factors across space and time. These models can account for spatial autocorrelation (the tendency of malaria cases to cluster geographically) and temporal dependencies (the influence of past malaria cases on current incidence).

- Explainable AI (XAI): Utilizing XAI techniques to understand the reasoning behind the model’s predictions is crucial. This helps in identifying the key environmental drivers of malaria outbreaks and building trust in the model’s output. XAI methods, such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), can be used to visualize the contribution of each input variable to the model’s predictions.

Enhancing Model Usability and Impact

Improving the practical application of these models is critical to ensuring their effectiveness in public health interventions.

- User-Friendly Interfaces: Developing user-friendly interfaces for public health officials is essential. These interfaces should allow users to easily access model predictions, visualize results, and understand the key drivers of malaria outbreaks. This might include web-based dashboards or mobile applications.

- Integration with Existing Public Health Systems: Integrating the model’s outputs into existing public health surveillance and response systems is crucial. This can involve sharing predictions with health workers, providing early warning alerts, and supporting targeted interventions such as insecticide-treated bed net distribution or indoor residual spraying.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Training: Engaging with public health stakeholders and providing training on how to use the models is essential. This will ensure that the models are effectively utilized and that the information they provide is understood and acted upon. This includes training on data interpretation, model limitations, and the appropriate use of the predictions in decision-making.

- Economic Analysis and Cost-Effectiveness Studies: Conducting economic analyses and cost-effectiveness studies to assess the impact of using these models for malaria control is important. This will help demonstrate the value of the models and justify investments in their development and implementation.

- Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: Establishing a system for continuous monitoring and evaluation of the models’ performance is crucial. This will allow for the identification of areas for improvement and ensure that the models remain accurate and relevant over time. This includes regularly assessing the models’ prediction accuracy, incorporating new data, and updating the models as needed.

End of Discussion

In conclusion, the marriage of remote sensing and predictive modeling offers a beacon of hope in the fight against malaria in Zambia. From understanding the disease’s complexities to forecasting outbreaks at a local level, this approach equips public health systems with the information needed to protect communities and allocate resources effectively. As technology advances, the accuracy and impact of these predictions will only grow, paving the way for a malaria-free future.

Essential FAQs

What is remote sensing?

Remote sensing is the science of obtaining information about an object or area from a distance, typically using satellites or aircraft to collect data about the Earth’s surface.

How does satellite data help predict malaria outbreaks?

Satellite data provides information on environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, and vegetation, which influence mosquito populations and malaria transmission. This data helps create models that predict outbreak risk.

What kind of satellite data is used?

Commonly used satellite data includes data from Landsat, Sentinel, and MODIS, which provide information on land surface temperature, vegetation indices, and rainfall patterns.

How accurate are these predictions?

The accuracy of predictions depends on several factors, including the quality of the data, the modeling techniques used, and the availability of ground-based data for validation. Continuous improvement is an ongoing process.

How can these predictions be used in the real world?

Predictions can be used to inform public health interventions, such as targeted mosquito control programs, distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets, and early diagnosis and treatment efforts. They also help in resource allocation.